News | February 5, 2013

Pacific locked in 'La Nada' limbo

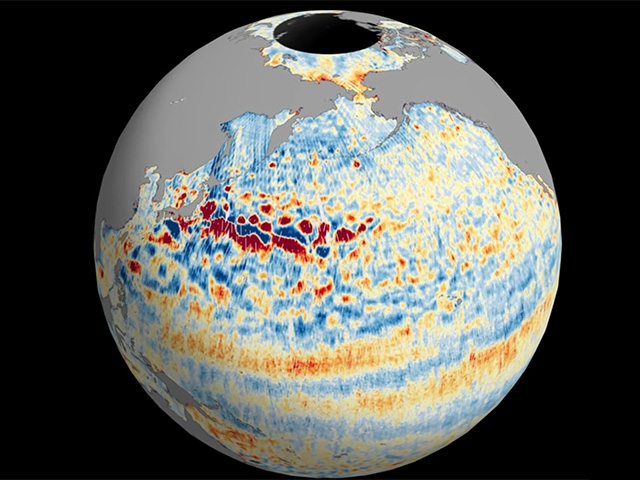

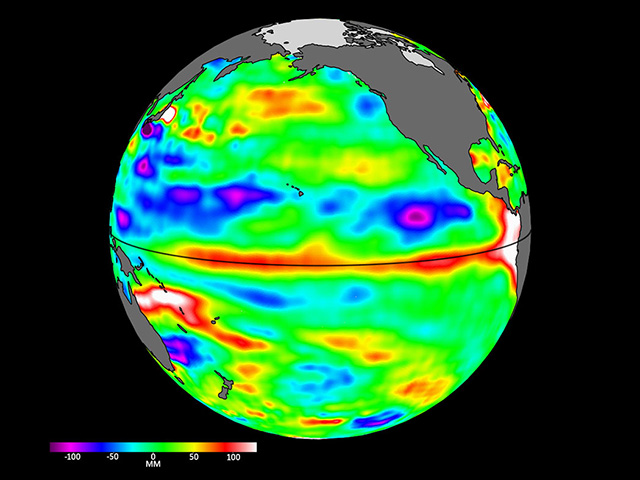

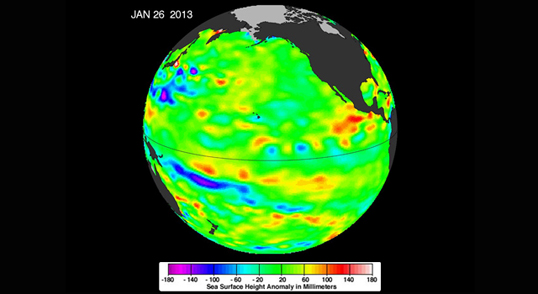

The latest image of sea surface heights in the Pacific Ocean from NASA's Jason-1 satellite shows that the equatorial Pacific Ocean is now in its 10th month of being locked in what some call a neutral, or "La Nada" state. "La Nadas" make long-range climate forecasting more difficult due to their greater unpredictability. Yellows and reds indicate areas where waters are relatively warmer and have expanded above normal sea level, while blues and purple areas show where waters are relatively colder and sea level is lower than normal. Green indicates near-normal sea level conditions. Image credit is NASA-JPL/Caltech/Ocean Surface Topography Team.

By Alan Buis,

Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Sea-surface height data from NASA's Jason-1 satellite show that the equatorial Pacific Ocean is still locked in what some call a neutral, or 'La Nada' state. This condition follows two years of strong, cool-water La Niña events.

A new image, based on the average of 10 days of data centered on Jan. 26, 2013, shows near-normal conditions (depicted in green) across the equatorial Pacific. The image is available at: http://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/images/latestdata/jason/2013/20130126P.jpg.

This latest image highlights the processes that occur on time scales of more than a year, but usually less than 10 years, such as El Niño and La Niña. These processes are known as the interannual ocean signal. To show that signal, scientists refined data for this image by removing trends over the past 20 years, seasonal variations and time-averaged signals of large-scale ocean circulation.

The height of the water relates, in part, to its temperature, and thus is an indicator of the amount of heat stored in the ocean below. As the ocean warms, its level rises; as it cools, its level falls. Yellow and red areas indicate where the waters are relatively warmer and have expanded above normal sea level, while green (which dominates in this image) indicates near-normal sea level, and blue and purple areas show where the waters are relatively colder and sea level is lower than normal. Above-normal height variations along the equatorial Pacific indicate El Niño conditions, while below-normal height variations indicate La Niña conditions. The temperature of the upper ocean can have a significant influence on weather patterns and climate. For a more detailed explanation of what this type of image means, visit: http://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/science/elninopdo/latestdata/.

"This past spring, after two years of La Niña, the expected El Niño was a no-show," says Bill Patzert, climatologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. "La Niña faded and 'La Nada' conditions locked in."

"This absence of El Niño and La Niña, termed 'neutral' by some, has left long-range climate forecasters adrift," Patzert added. "Seasonal, long-range forecasting works best when signals like El Niño and La Niña are strong." Patzert calls the present condition 'La Nada,' because the word 'neutral' misleadingly implies to some that weather will be 'normal.'

"For me 'normal' is the cycle on a washing machine," Patzert said. "I never say the word 'normal' when it comes to winter weather in the American West. For instance, in the last 100 years, we've only had a total of six 'normal' years of rainfall in Los Angeles, meaning about 15 inches of rain per winter in downtown L.A. Historically, La Nadas have delivered both the wettest and driest winters on record. For long-range forecasters, La Nada is a teeth grinder." NASA scientists will continue to monitor this persistent La Nada - now in its 10th month -- to see what the Pacific Ocean has in store next for the world's climate.

The comings and goings of El Niño, La Niña and La Nada are part of the long-term, evolving state of global climate, for which measurements of sea surface height are a key indicator. Jason-1 is a joint effort between NASA and the French Space Agency, Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES). Jason-2 is a joint effort between NASA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, CNES and the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT). JPL manages the U.S. portion of both missions for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. In early 2015, NASA and its international partners CNES, NOAA and EUMETSAT will launch Jason-3, which will extend the timeline of ocean surface topography measurements begun by the Topex/Poseidon and Jason 1 and 2 satellites. Jason-3 will make highly detailed measurements of sea level on Earth to gain insight into ocean circulation and climate change.

For more on NASA's satellite altimetry programs, visit: http://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov.