News | February 9, 2016

2016 El Niño: Don't mock the croc

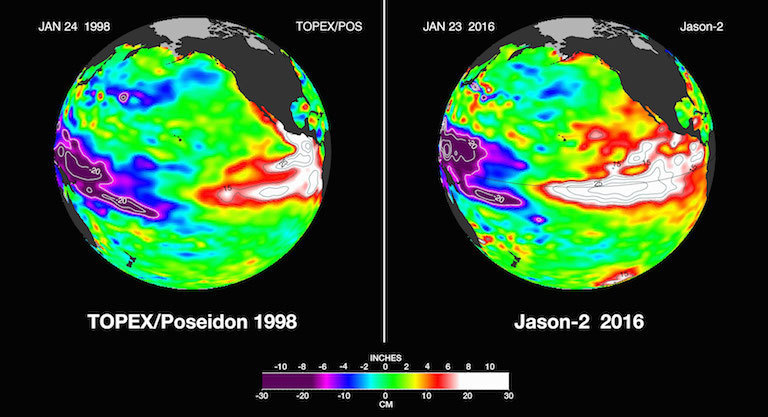

Satellite images of strong El Niños, in 1998 and today. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The large and powerful El Niño in the eastern tropical Pacific has yet to deliver torrential rains to Southern California—an almost daily problem for Bill Patzert, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s quotable oceanographer.

“No matter where I go—whether it’s JPL or Whole Foods or talking with reporters—everybody has a simple question: Show me the rain,” Patzert says.

But it might just be a case of expectations outrunning El Niño itself.

The massive pool of warm water now parked off Central America’s west coast remains formidable, and invites comparisons to the 1998 El Niño, remembered for pummeling rains that brought flooding, mud slides and debris flow to much of Southern California.

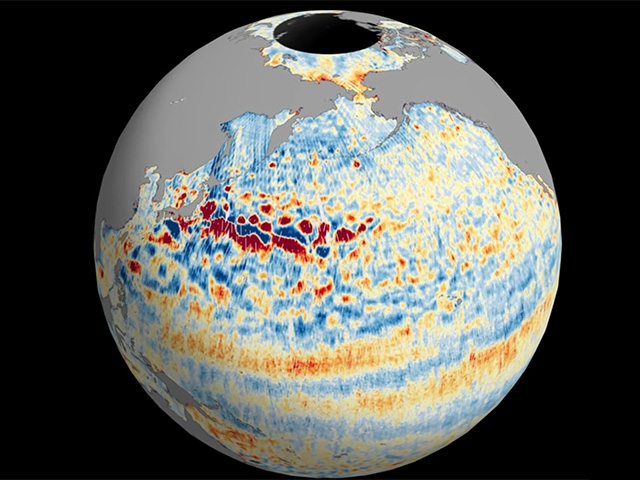

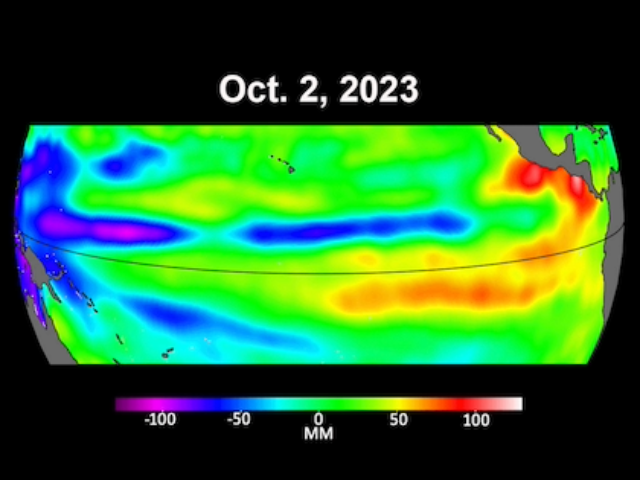

If anything, the shape of this zone of elevated sea surface height—corresponding to a warming-induced increase in ocean water volume—looks more menacing than its late ’90s predecessor.

To Patzert’s eye, the Jason 2 satellite’s image of the 2016 El Niño looks a lot like a crocodile, complete with an eye and a tapered snout.

“The 2016 croc definitely has legs,” Patzert says. This year’s El Niño “is definitely longer lasting and reaching its peak much later than in ’98.”

His message: “Don’t mock the croc. It’s still a big deal.”

While El Niño has delivered some rain, improving California’s vital snow pack, the Pacific phenomenon’s late peak could mean that heavier downpours are only weeks away.

“Historically, El Nino has put on the big show in February and March,” Patzert said.

Still, predicting El Niño’s behavior is always a tricky business.

“By late February, I’ll be nervous if something hasn’t happened,” he said.

For now, he says, all eyes are on JPL’s images from space.

“Our sea level images have become the poster child for El Niño,” he says.

This article was originally posted on NASA Sea Level Change: Observations from Space.