News | September 15, 2009

Space age water gauge

Using satellite imagery, scientists have come up with a clever way to map agricultural water consumption. The technique may ultimately help us to better manage our precious water resources.

Planet Earth should really be called “Planet Ocean”, because 70 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered by water. Of the 326 million cubic miles of water

Freshwater scarcity is becoming an increasing concern, with some arguing that it will become one of the world’s most important issues this century, exacerbated as it will be by population growth and harsher droughts arising from climate change. Agriculture is a major cog in the water wheel: worldwide, 70 percent of all the water withdrawn for human use is devoted to land irrigation. It’s also responsible for a lot of wastage: according to the International Water Management Institute, while it currently takes 1,000 to 2,000 liters of water to produce a kilogram of grain, the same could be done with as little as 500 liters.

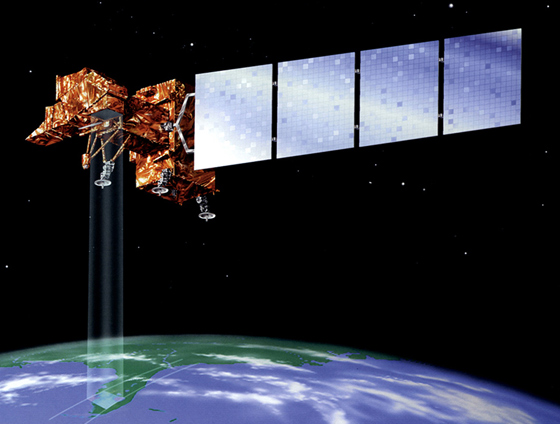

Using satellite imagery, scientists have come up with a clever way to map agricultural water consumption, which may ultimately help us to get more crop per drop. In a new video released by NASA (below), water specialists Rick Allen, Bill Kramber and Tony Morse describe their “Mapping Evapotranspiration” technique, which, using spaceborne instruments, tracks the amount of heat in fields and reveals clues about water use in that area.

Evapotranspiration is an important part of the water cycle involving vegetation. It describes the amount of water that evaporates directly from the soil plus the amount of transpiration – the release of water – through plant leaves. Water taken away by evapotranspiration carries heat energy with it, so farm fields consuming more water appear cooler. While these soil temperature differences are invisible to the eye, they can be picked up by infrared instruments on NASA’s Landsat satellite, and can tell us whether or not there is enough water to supply the needs of the plants.

Mapping evapotranspiration offers an objective way for water managers to assess on a field-by-field basis how much water agricultural growers are using. The team’s measurements have even been used to help settle water rights conflicts in court. In recognition of the innovation, Harvard University’s Ash Institute awarded the work a prestigious Innovations in American Government Award. More innovations in water resource management are likely to come from space satellites and the unique vantage point that they offer us.

Dr. Amber Jenkins Global Climate Change Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Video produced by Jennifer Shoemaker NASA Earth Science Multimedia Team