Ask NASA Climate | April 19, 2011, 17:00 PDT

Adventures from planet Earth

Call of the snow

By Dr. Tom Painter, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory Reporting from the mountains of Colorado

I get to study planet Earth for a living. Two weeks ago I was at the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in Vatican City discussing mountain glaciers, and this week I’m in sustained snowfall in Colorado. Today, we are hunting dust in the high mountains of the Colorado River Basin. At the Vatican we were exploring what has caused the loss of mountain glaciers in the “Anthropocene” — the last two centuries during which humans have become a geologic force through their impacts on the Earth system. We have considered this to be exclusively the domain of the increases in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that have accompanied industrialization, and caused more heat to be trapped near the surface of the planet. Sure enough, that alone has been a powerful force, but there is much more to the story that involves the vast transformation of the land surface around much of the globe.

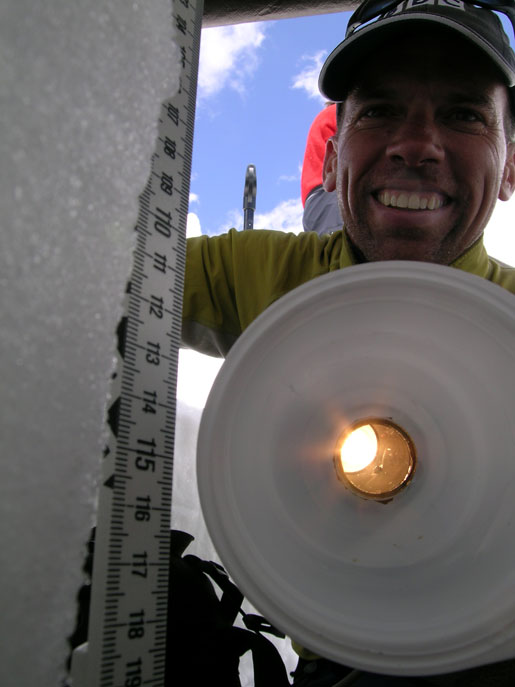

In Colorado, we are looking at the impacts that humans have had on the mountain snowpack — in the mid 1800s, industrialization facilitated the injection of the railroad into the interior of North America and, of course, what is now the western United States. With the railroad came the cattle and sheep and our capacity to inhabit the interior. As a result of widespread grazing and other disturbances of the fragile desert surfaces, the amount of dust put into the air and deposited in the mountain snow has increased five-fold. This dust darkens the snowpack and makes it melt faster — in the case of Colorado, the snowpack melts about a month earlier than it would without the increase in dust.

I’ve been doing this work for 17 years. My colleagues and I often get comments from the uninitiated that this mountain snow research is simply a chance for a skiing holiday. Once they’ve tried to hang in there for a day, they realize that working in the mountains can in fact be punishing. Twelve-hour days schlepping one’s pack full of safety gear, field equipment, plenty of water and food and then the 30-lb spectrometer on top of it all, while sucking in about 40 percent less oxygen than at sea level. The skiing is … well … not exactly the groomed slopes at Vail [Ski Resort in Colorado].

Conditions range from bulletproof wind pack to plunging three feet deep in hollow slush. I’ve often seen my former racer colleagues double-eject from their ski bindings while twisting to preserve the snow samples and equipment. And then the weather — high winds, blinding snow fall, lightning and thunder, electric-sparking snow probes and skis, and, as my collaborator Chris Landry puts it, “severe clear solar storming,” — days that are cloudless and windless that cook your face and overheat you more than in the Sahara. And yet all this suffering is no match for the need to know what is happening to that complex beast, the mountain snowpack.

Even in the stunning beauty of the Casina Pio IV, the home to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and immersed in intense discussions with some of the best snow and ice scientists in the world, the call of the mountains was strong. The more I talked about the snow, the more I felt the need to touch it, look at it and understand it. And now, I am here — just about to buckle my ski boots for the hunt.

Tom is a research scientist in the Water and Carbon Cycles Group at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He studies the effect of dust on snow pack and snow melt around the world, and the implications this has for water supplies.