Ask NASA Climate | November 8, 2023, 12:00 PST

Vanishing Corals, Part Two: Climate Change is Stressing Corals, But There's Hope

The Landsat 8 satellite’s Operational Land Imager captured this image of coral reefs in the northern Great Barrier Reef, Australia, on August 22, 2020. The Great Barrier Reef is the largest reef system in the world. Satellites provide scientists with important information on the environment around coral reefs, including ocean temperatures and water quality. This helps them understand changes to corals over time. Credit: NASA

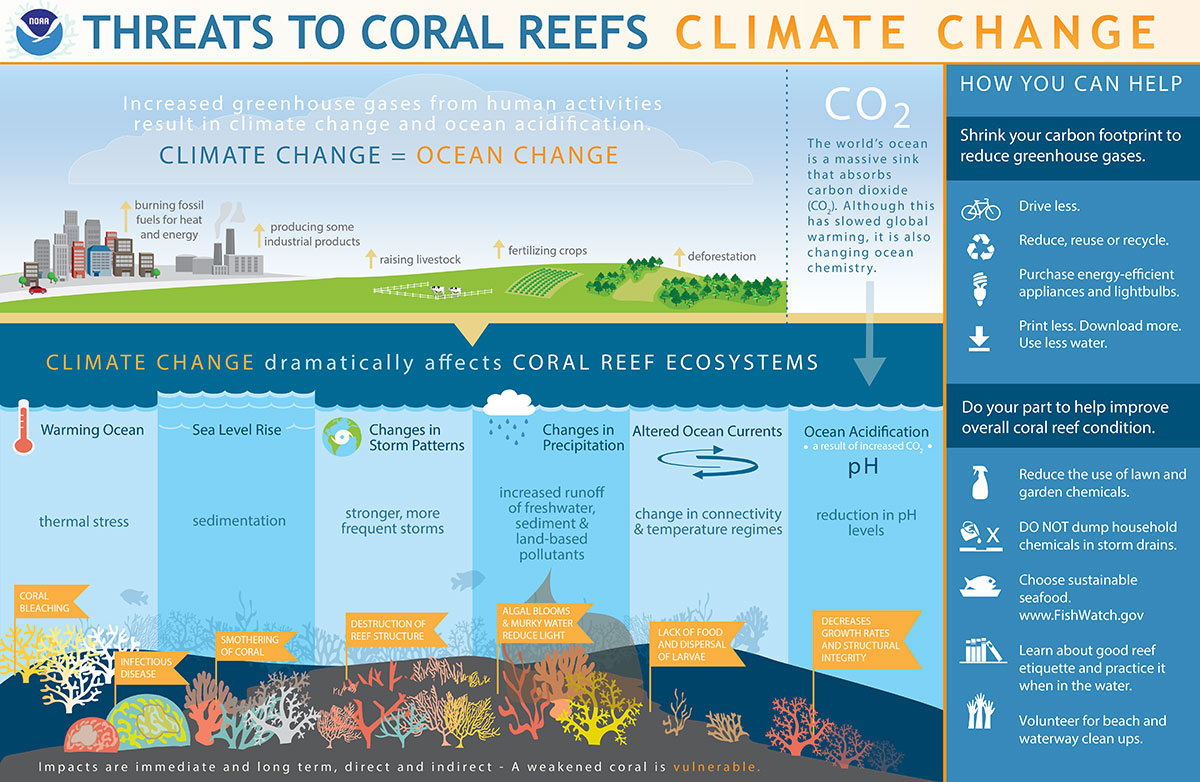

Coral reefs are one of the most important ecosystems in the world. Together they support over a quarter of all known marine species, protect coastlines during storms, and help local economies through fisheries and tourism. However, decades of data, collected in part from NASA’s airborne and satellite missions, show that corals are declining rapidly. Human actions, like burning fossil fuels, are shifting our global climate by warming the air and ocean. But that isn’t the only way: Pollution and physical damage from ships and divers also play a role.

Let’s dive deeper into the different ways that humans are impacting corals.

The burning of fossil fuels has been the main driver of ocean warming since the 1970s. Based on NASA’s Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean (ECCO) project, the total heat stored by the oceans (ocean heat content) rose 187 zettajoules from 1992 through 2019. And most corals can’t take the heat.

According to Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, professor of marine studies at the University of Queensland in Australia, corals are fine-tuned to their environment. Thus, even small changes in temperature can stress a coral out. This can lead to coral bleaching.

Bleaching occurs when stressed corals expel their zooxanthellae, revealing their underlying white skeleton. Once a coral is bleached, it becomes more vulnerable to any additional stressors, including those from diseases and storms. Historically, corals would have 20 years or so to recover between stressful events (marine heat waves or cold spells, disease, or storms). However, with climate change, the frequency of events like marine heat waves, is increasing, leaving corals with insufficient time to recover. Over time, this leads to the loss of habitat for the thousands of marine creatures that depend on the reef for survival.

Warming water isn’t the sole issue. The ocean also acts as a sponge that absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere -- and human activities have produced a lot of it. This increase in carbon dioxide causes the ocean to become more acidic, which is now happening at a rate faster than at any time in the past 300 million years.

“If you put a coral skeleton into a soda, the soda’s acid will dissolve it in about an hour,” said Ved Chirayath, professor of Earth sciences at the University of Miami in Florida. “Similarly, as the ocean becomes more acidic, corals struggle to make their structures and can’t grow as quickly.”

This is because coral skeletons are made from a type of calcium carbonate. When carbon dioxide is added to ocean water, chemical reactions lead to carbonate ions bonding with excess hydrogen ions instead of with calcium ions. Essentially, less calcification occurs, which makes it harder for skeletons to grow. If the water becomes too acidic, it can begin to dissolve the skeletons themselves.

While climate change is the primary factor disrupting coral reefs, other human actions also contribute to their decline. “Pollution -- including chemicals, fertilizer, and other toxins that travel from the land into the ocean -- is also a problem,” stated Liane Guild, research scientist with NASA’s Ames Research Center in California and a representative on the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force (USCRTF).

“Divers or commercial fishermen who don’t know how to properly treat a reef can also cause physical damage,” added Juan Torres-Pérez, research scientist with NASA Ames and a representative on USCRTF. Physical damage can include breaking a coral by accidentally stepping on it or dropping an anchor on it, as examples.

All of these impacts combined have led scientists to conclude that human actions are the primary cause of the observed global decline in corals. “If you look at the rate of decline, it is human-driven. There is no other explanation,” said Hoegh-Guldberg.

Since human actions are the problem, can we do anything to help corals survive?

Current predictions for emissions of greenhouse gases place almost all reef corals on a path toward near extinction without human intervention. “Taking urgent action to get to pre-industrial emission levels will allow corals and other life to rebound,” said Chirayath. “It’s up to us, as the species who rapidly changed the climate, to change it back.”

Some corals are adjusting. “There are these amazing adaptations that corals are doing as they find ways to survive in harsh conditions,” said Guild. For example, a recent study found that some reefs in the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean are becoming more heat tolerant by being able to change which algae, or zooxanthellae, they host. Scientists are working to identify these resilient corals and develop methods to grow and reintroduce them into the ocean.

The success of these corals gives many scientists hope, but they know that corals can’t do it alone. NASA is helping in part by sharing its decades of data with the world. For example, in a recent NASA-partnered study, scientists used satellite data to give people important information about their local reefs so that they could take actions to protect them.

To continue exploring how scientists are using NASA data in addition to water surveys to monitor the health of coral reefs around the world, check out Vanishing Corals, Part One.