Ask NASA Climate | February 6, 2011, 16:00 PST

Out of this world?

The Mars climate change mystery

By Erik Conway NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Mars has been a grand scientific mystery ever since the first modern images were beamed back from the Mariner 4 spacecraft in 1965. Those snapshots showed a moon-like, cratered surface — not what we expected. Scientists had assumed that Mars would have an Earth-like atmosphere, composed mainly of nitrogen and with traces of carbon dioxide and water vapor. What they found instead was a cold desert world, one that possessed a thin wisp of an atmosphere containing only carbon dioxide.

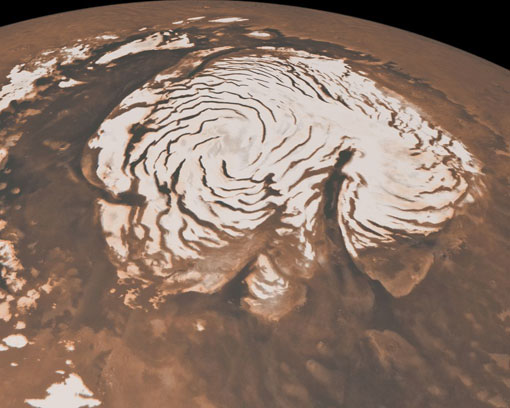

Subsequent missions to the Red Planet detected tiny amounts of water vapor in Mars’ atmosphere, and better images began to unveil what looked like river channels and deltas on the surface. Indeed, spacecraft launched in the late 1990s and 2000s found water on Mars in the form of ice, bound into the planet’s soil and in great underground deposits. Water used to flow on the surface of Mars. But how? And where did it all go?

At first sight, the facts defy logic. According to astronomers, the sun used to be dimmer (i.e. colder) than it is now, meaning that Mars (and Earth) should have been colder in the past, not warmer. But observations tell us that it was clearly warmer and wetter on Mars in the past — not colder and more frozen. How did Mars buck the trend and stay toasty in the past? The most likely answer is that it used to have some sort of “super greenhouse effect” going on, the like of which we see on Venus. On Venus, the thick carbon-dioxide-based atmosphere traps the sun’s heat, resulting in surface temperatures that are hot enough to melt lead. Scientists think that early Mars also had a thick, carbon-dioxide-rich atmosphere that provided warming.

That said, in a recent talk at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco, Mars specialist Bruce Jakosky of the University of Colorado pointed out that heat-trapping carbon dioxide alone would not have been sufficient to make Mars warm enough and wet enough to match our observations. Carbon dioxide’s ability to trap heat would have at some point “saturated”, or maxed out. Other greenhouse gases, like methane or ammonia, might have helped trap more heat near the surface of Mars — but they would not have been sufficient either because the sun’s ultraviolet radiation would have destroyed them far too quickly. Ergo, some sort of ultraviolet-absorbing layer high in Mars’ atmosphere would have been needed to help trap the heat. (The Earth’s ozone layer, which dates back to somewhere between 2 and 2.7 billion years ago, performs this service for us now.)

There is, as yet, no evidence of the necessary chemicals on Mars to do this. Jakosky didn’t draw any firm conclusions about how the warmer Mars could have existed. But he did lay out possible future investigations that might help uncover parts of this mystery a little more clearly. One of those includes the MAVEN mission to Mars, scheduled for launch in 2013, which will study how Mars’ atmosphere and climate has changed over time.

As Jakosky has said, in some ways, Mars is a very Earth-like planet. By looking at conditions on other worlds, we can gain insights into how, and why, our own climate is changing here on planet Earth.

You can read more about the Mars Science Laboratory rover here. Scheduled for launch in the fall of 2011, the Curiosity rover will help determine whether Mars has in the past, or does today, harbor life.