Ask NASA Climate | July 14, 2016, 14:45 PDT

Shuffle and flow: Where does carbon come from, and where does it go?

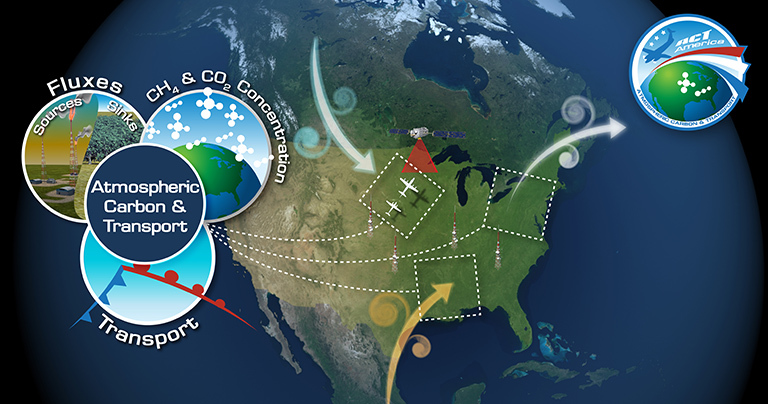

Atmospheric Carbon and Transport (ACT) - America

ACT-America, or Atmospheric Carbon and Transport – America, will conduct five airborne campaigns across three regions in the eastern United States to study the transport and fluxes of atmospheric carbon dioxide and methane.

The average amount of carbon dioxide in Earth’s global atmosphere is 400 parts per million (ppm), but according to Ken Davis, Atmospheric Carbon and Transport - America (ACT-America) principal investigator, areas near agriculture like cornfields can consistently run about 10 ppm lower in the summertime. That’s because terrestrial ecosystems like trees and corn suck about a quarter of our carbon dioxide emissions out of the atmosphere.

Thank you, trees and corn.

But wouldn’t you like to know exactly where this is happening, and by how much? Does the amount of carbon dioxide taken up by farms and forests change across seasons, across weather patterns? And even more important, will these ecosystems still be able to continue pulling our carbon pollution out of the atmosphere for us 50 years from now, especially if our climate changes unfavorably for these biological systems? Will dead trees start releasing carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere? It’s as if the forests and farms are “Get Out of Jail Free" cards and we’re not sure for how long the free pass will be good.

It’s as if the forests and farms are “Get Out of Jail Free" cards and we’re not sure for how long the free pass will be good.

See, scientists have been measuring carbon dioxide and methane on a global basis. But we’d like to understand the mechanisms that are driving biological sinks and sources regionally. And we’d like to measure these greenhouse gases so that we can know if and when we’ve succeeded in reducing our emissions.

Davis explained that right now, most of our knowledge about regional sources of methane and carbon dioxide comes from a ground-based network of highly calibrated instruments on roughly 100 towers across North America. Yet being able to understand the regional sources and sinks of these two greenhouse gases is crucial to being able to predict and respond to the consequences of a changing climate.

“We don’t have all the data we need? That’s unbelievable,” I said, shocked. How is that even possible in 2016?” But Davis kept repeating: “No, we definitely don’t have enough data density.” Indeed, we take our data for granted, even as we continue burning fossil fuels.

So on July 18th, Davis and his team will head out to the first of three study areas for a two-week stint. These three regional study areas were chosen to represent a combination of weather and greenhouse gas fluxes across the U.S. The Midwest has a lot of farms and therefore has an agricultural signal. It’s also the origin point of cyclones. The Northeast forests are different than the Southern coastal forests, which will give us both types of data. The Southern coastal weather, storms and flow off the Gulf of Mexico are unique, and there’s oil and gas development in both the Mid-Atlantic and Southern regions. This means that between these three study areas, the team will be able to observe a wide range of conditions.

In addition to measuring regional sources and sinks of carbon dioxide and methane, ACT-America is planning to fly on a path right underneath NASA’s OCO-2 satellite to measure air characteristics, provide calibration and validation and make OCO-2’s data more useful. The mission will also fly through a variety of weather systems to find out how they affect the transport of these greenhouse gases.

Davis told me he’s “excited to fly through cold and warm fronts and mid-latitude cyclones to find out how greenhouse gases get wrapped up in weather systems.”

Find out more about ACT-America here.

Thank you for reading.

Laura

ACT-America is part of NASA Earth Expeditions, a six-month field research campaign to study regions of critical change around the world.