Ask NASA Climate | May 20, 2015, 09:07 PDT

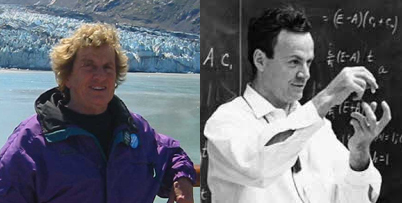

The sun is always shining on Joan Feynman

A solar filament eruption. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Solar Dynamics Observatory.

Joan and I were supposed to be discussing her work on sunspots, aurora, geomagnetism and solar winds but we kept veering off on tangents, and I’m certain it was all my fault. I was charmed by her Long Island accent and wacky sense of humor, and the fact that at 88, she holds a research position at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

But Joan is much more than a little sister and a funny storyteller: She’s a legit solar physicist who spent a long career analyzing the patterns of sunspot frequencies and their relationship to aurora. You see, people who live meaningful lives look deeply at the world around them—deeply enough to be moved, and sometimes deeply enough to move others. So in one afternoon, she managed to transfer a bit of her passion to me. I became mesmerized, mind-blown and in awe of solar physics.

“People have been observing aurora and drawing pictures of them for thousands of years,” she explained. “We have records of them from the year 450 C.E. to 1450 C.E. The Swedes and Norwegians had made lists of what days there were aurora and the Chinese made lists. So they knew that when there was a big aurora in China, there was a big aurora in Sweden.”

She went on to describe how “aurora, the geomagnetic currents and solar flares are part of the same process. Solar flares put out huge disturbances in the magnetic field of the solar wind and in the kind of particles that come out, and they cause the aurora.” Solar geomagnetic activity varies over 11-year and 88-year cycles. The 88-year Gleissberg cycle, a variation in amplitude of the 11-year solar cycle, is what’s captivated Joan throughout her career. “The whole point of science is to understand the mysteries you see around you,” she said. And solar activity has been part of that mystery for Joan her entire life.

Check out this story about the first time she saw an aurora as a very young child: “One night I had already gone to bed. I was supposed to stay in bed, but my brother got permission to come in and wake me up because there was an aurora in the sky over the golf course near our home in Long Island. It looked to me like marvelous lights in the sky moving back and forth. It was very impressive to me. My brother said to me that nobody knows what that’s from, which was true in 1930.”

“I was fascinated by that aurora,” she continued. “They’re gigantic, they’re impressive; everybody runs out to see them. They were mysteries. The sky is lit up red and gold and yellow and shooting.”

When I told her that I didn’t even know they had aurora in Long Island, she said, “Auroras come down to lower latitudes when they’re very big.”

Are you starting to see how I got all jacked up just listening to her? I’ve never even seen a real live aurora. It was like sitting next to a kid with a better toy. She was taunting me, describing colors, movement and wild sky. I was hooked and jealous.

I want to see one now!

Although today we understand that aurora are caused by the interaction between the Earth’s magnetosphere and the magnetic particles in the solar wind, there are still plenty of solar mysteries to keep Joan occupied. “How does the sun do that?” She wants to know. “How does the sun manage to get a cycle of 88 years?”

For me, the question is clear: “If there were lots of them in the 1930s, and there’s an 88-year cycle, does that mean I’m going to get to see them soon?”

She answered: “It’s time for me to write the next paper on this! Are they back?”

I look forward to your comments.

Laura