Ask NASA Climate | December 14, 2009, 16:00 PST

Inside Copenhagen

The challenge of atmospheric bookkeeping

Dr. Tony Freeman, Earth science manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, is in Copenhagen attending what is being billed as a historical climate summit. This is the third of his dispatches from the negotiations.

On Thursday I sat in on a press conference given by Professors Ray Weiss and Tony Haymet of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography. The title of their talk was “Trust but Verify: Why Climate Legislation and Carbon-Equivalent Trading Need Atmospheric Emission Verification to Work.” Weiss described his research into some key molecules — CF4 (carbon tetrafluoride), NF3 (nitrogen trifluoride), SF6 (sulfur hexafluoride) and HFC-134 (hydrofluorcarbon-134) — all long-lived gases that can stick around for up to 50,000 years in the upper atmosphere. Their longevity is worrying because we know that they break down the ozone layer that protects us on the surface of the Earth from harmful UV radiation — in other words, they help create the ozone hole. They are also greenhouse gases, because they help to trap heat in the lower atmosphere. All four of these molecules are controlled under the Montreal Protocol, a treaty that was agreed to in 1989 and that Kofi Annan, former secretary general of the U.N., has called “perhaps the single most successful international agreement to date.” But Weiss’ results show that the concentrations of these gases measured in the atmosphere are far in excess of the numbers reported by the industries that produce them. Why are the numbers off? There are just a few hundred industrial facilities worldwide that release these gases, so counting up their emissions should be fairly straightforward. Weiss and Haymet say that we need some proper bookkeeping of emissions to keep industries in check. The next day, I listened to a keynote speech given by Professor Paul Crutzen, the Dutch atmospheric chemist who received the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1995 for his work on the ozone hole. Crutzen was part of a group of scientists who urged the world to act to control the release of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) — two families of ozone-damaging chemicals — into the atmosphere. While there is a parallel between CFC and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, Crutzen explained, the problem with CO2 is that there are tens of thousands of emission sources — power plants, steel-making facilities, oil refineries, the burning of wood, vegetation (‘biomass’), particularly in tropical regions, and so on. What’s more, the generation of CO2 from these activities is intimately linked to economic growth, which compounds the problem of making sure that emissions are accurately reported. It’s also one of the major reasons why getting the world’s leaders to sign up to a global climate treaty is so difficult.

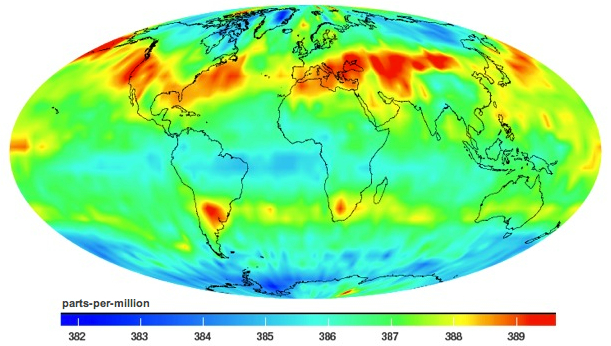

Dr. Takashi Moriyama of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, who was up next, made an interesting point, and one that is obviously close to NASA’s heart. He argues that the only effective way to monitor and attribute CO2 emissions is to use the same vantage point from which scientists watched the evolution of the ozone hole — which means from space.

--Tony Freeman