Ask NASA Climate | March 21, 2010, 17:00 PDT

Cruisin' the Northwest Passage

Holy grail now a tourist route

From Dr. Tony Freeman, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Searching for vacation ideas recently on the web, I came across a recommendation by the intrepid “Man vs. Wild” TV survival expert, Bear Grylls. His tip referred to a tour company offering a cruise of the Northwest Passage — a sea route in the Arctic Ocean that connects the North Atlantic to the North Pacific Ocean. The tour covers over 2500 miles (4000 kilometers) from Resolute in Nunavut, Canada (which is also known as the “place with no dawn”), to Cambridge Bay in Nunavut. The fact that such tours exist brought home to me both the rapidity of climate change in the Arctic, and a perhaps unanticipated benefit.

Growing up in the second half of the twentieth century, the Northwest Passage was to me the stuff of fable and legend, straight from the great age of exploration. Such a passage would connect Europe to Asia via a shorter route and avoid the long journey south around Africa. For centuries, the passage has been sought by explorers as a possible trade route. Unsuccessful attempts were made by several famous figures including Sir Francis Drake, John Cabot, Sieur de La Salle, Jacques Cartier and, a great hero of mine, Captain Cook. In 1845 Sir John Franklin’s famous expedition to find the Northwest Passage floundered in the ice, with all hands lost to starvation, exposure and perhaps worse. Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen was more fortunate, and in 1906 he completed the first successful navigation of the Northwest Passage, but only by taking a route south of Victoria Island. His journey was fraught with danger — it took three years in a converted herring boat, with winters spent trapped in the ice waiting for the frozen sea around them to thaw.

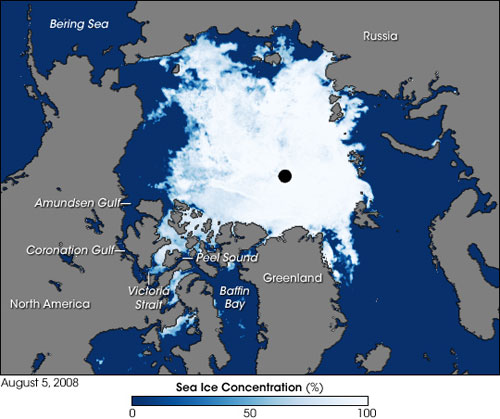

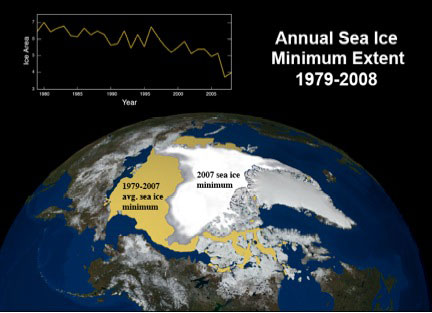

In the summer of 2007, Arctic sea ice reached a record low and the fabled passage saw enough ice melt to make navigation feasible. The global significance of this opening, which is clearly visible in NASA’s satellite data, is that it represents a shorter trade route for ships traveling between the Northern Pacific and Northern Europe in comparison to the Panama Canal route, and could make large-scale Arctic shipping possible. But to me, declaring the Northwest Passage open for tourism is like announcing day trips to Eldorado, or submarine cruises to Atlantis, or charter flights to Shangri-La.

Tony Freeman is an Earth science manager at JPL.