Ask NASA Climate | September 8, 2010, 17:00 PDT

Flight of fancy

It's a bird. It's a plane. It's a hurricane.

From Dr. Bjorn Lambrigtsen, Group Supervisor, Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Last week NASA’s unmanned Global Hawk plane successfully flew over a fully-formed hurricane for the first time. It took off from NASA's Dryden facility at Edwards Air Force Base near Mojave, Calif., at 9 p.m. the previous evening. After climbing above 50,000 feet (15 kilometers) to get out of airline traffic lanes, it flew across the southern U.S. to the Gulf and across Florida, and found the storm eight hours later, flying over the hurricane for another eight hours. By that time it had climbed to 60,000 feet (18 kilometers).

This was all as part of NASA’s 2010 “GRIP” (Genesis and Rapid Intensification Processes) field experiment — a mission designed to study how tropical storms form and develop into major hurricanes.

Although the Global Hawk flies itself per a flight plan stored in its computer, there are experienced pilots monitoring it from a control center at Dryden, and from time to time they intervene by uploading a revised flight plan. There is no joystick — everything is done with a keyboard and mouse via a graphical user interface (GUI). One of the things the ‘pilots’ look for is cloud tops near or above the flight altitude, which might be associated with dangerous turbulence that could possibly endanger the plane. The plane hosts a forward-looking video camera as well as a downward-looking fish-eye lens camera, and they are used in daylight. There is also an accelerometer on board (think the device inside your Wii controller).

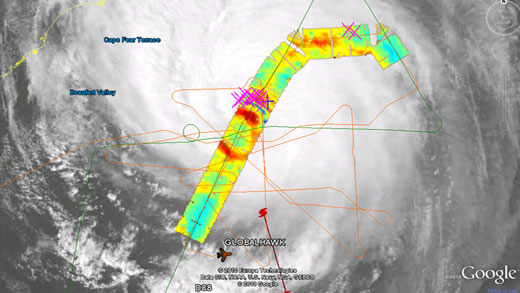

One of the payloads on the Global Hawk is the High Altitude MMIC Sounding Radiometer (HAMSR), an instrument that can measure air temperature, precipitation, ice content in clouds, and convection in the atmosphere. We had three shifts covering this 24-hour flight. Yours truly hit the freeway at 3 a.m. to catch the flight portion over Hurricane Earl. We got some really good measurements while flying straight across the eye of the storm several times, since it turned out that the cloud tops were well below flight altitude. With the data we collected, we will now be able to study the process of "hurricane eyewall replacement", a process by which the eyewall — a ring of thunderstorms that surrounds the eye of the storm — reorganizes itself and enables the storm to re-strengthen.

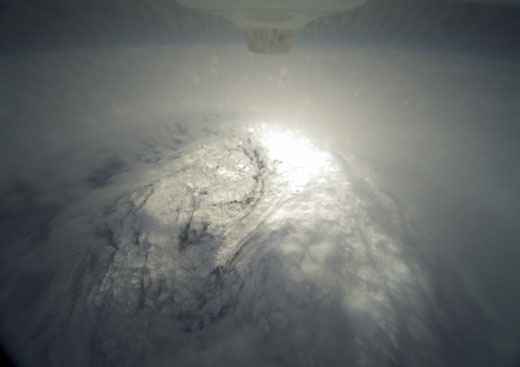

The photo above shows the view from the plane’s belly camera while approaching the eye of the storm (the top of the photo looks forwards and the bottom of the photo looks straight down). The image below is a sample quick-look image from HAMSR taken as the Global Hawk passes over the eye. The eye can be seen as the blue-green area (ocean surface plus light clouds) surrounded by an orange-red ring (clouds). The blue patch just north of the cloud ring indicates a convective burst, probably a thunderstorm. That is confirmed by the pink crosses, which indicate lightning.

More images can be found at the HAMSR browse page and at the JPL hurricane portal.

Bjorn specializes in studying the Earth's atmosphere using microwaves. His research activities range from developing new technology such as HAMSR to studying hurricanes. He is the Microwave Instrument Scientist for the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS instrument) carried on NASA's Aqua satellite.