News | May 1, 2013

NASA rover prototype set to explore Greenland ice sheet

NASA Headquarters

María-José Viñas,

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

NASA's newest scientific rover is set for testing May 3 through June 8 in the highest part of Greenland.

The robot known as GROVER, which stands for both Greenland Rover and Goddard Remotely Operated Vehicle for Exploration and Research, will roam the frigid landscape collecting measurements to help scientists better understand changes in the massive ice sheet.

This autonomous, solar-powered robot carries a ground-penetrating radar to study how snow accumulates, adding layer upon layer to the ice sheet over time.

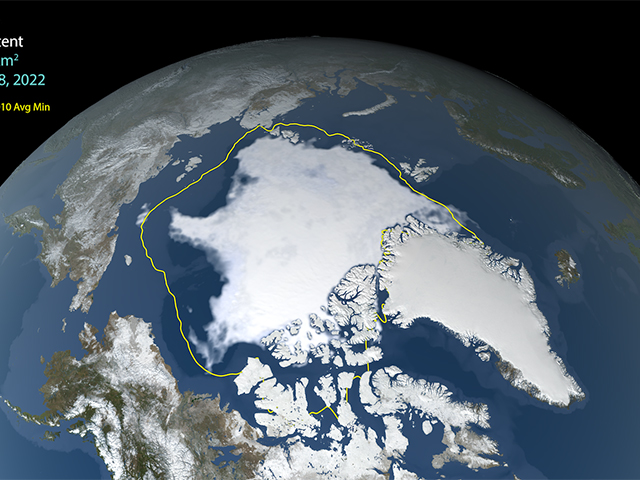

Greenland's surface layer vaulted into the news in summer 2012 when higher than normal temperatures caused surface melting across about 97 percent of the ice sheet. Scientists at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., expect GROVER to detect the layer of the ice sheet that formed in the aftermath of that extreme melt event.

Research with polar rovers costs less than aircraft or satellites, the usual platforms.

A prototype of GROVER, minus its solar panels, was tested in January 2012 at a ski resort in Idaho. The laptop in the picture is for testing purposes only and is not mounted on the final prototype. Credit: Gabriel Trisca, Boise State University

A prototype of GROVER, minus its solar panels, was tested in January 2012 at a ski resort in Idaho. The laptop in the picture is for testing purposes only and is not mounted on the final prototype. Credit: Gabriel Trisca, Boise State University"Robots like GROVER will give us a new tool for glaciology studies," said Lora Koenig, a glaciologist at Goddard and science advisor on the project. GROVER will be joined on the ice sheet in June by another robot, named Cool Robot, developed at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., with funding from the National Science Foundation. This rover can tow a variety of instrument packages to conduct glaciological and atmospheric sampling studies.

GROVER was developed in 2010 and 2011 by teams of students participating in summer engineering boot camps at Goddard. The students were interested in building a rover and approached Koenig about whether a rover could aid her studies of snow accumulation on ice sheets. This information typically is gathered by radars carried on snowmobiles and airplanes. Koenig suggested putting a radar on a rover for this work.

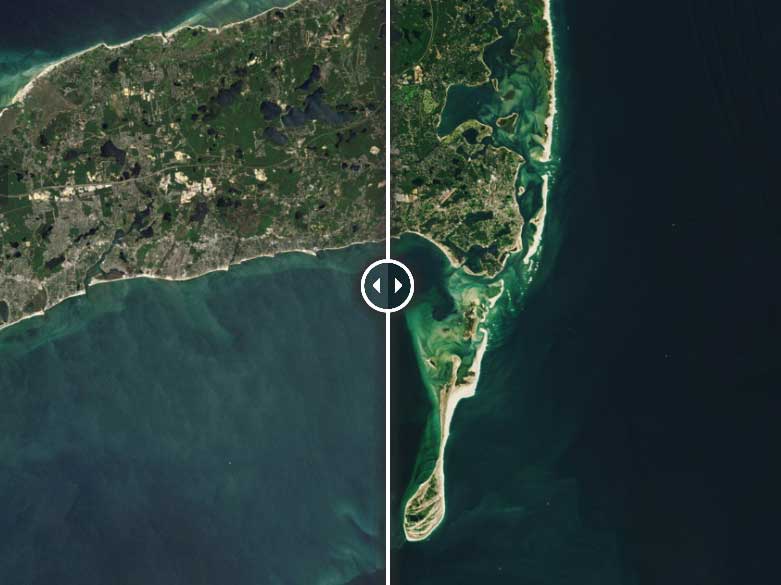

Students from a NASA Goddard summer engineering boot camp test two prototypes of GROVER at a beach in Asseteague Island, Md., in 2011. The prototype in front is similar to the one NASA will test in Greenland in May 2013. Credit: NASA/Michael Comberiate

Students from a NASA Goddard summer engineering boot camp test two prototypes of GROVER at a beach in Asseteague Island, Md., in 2011. The prototype in front is similar to the one NASA will test in Greenland in May 2013. Credit: NASA/Michael ComberiateKoenig, now a science adviser on the GROVER Project, asked Hans-Peter Marshall, a glaciologist at Boise State University to bring in his expertise in small, low-power, autonomous radars that could be mounted on GROVER. Since its inception at the boot camp, GROVER has been fine-tuned, with NASA funding, at Boise State.

The tank-like GROVER prototype stands six feet tall, including its solar panels. It weighs about 800 pounds and traverses the ice on two repurposed snowmobile tracks. The robot is powered entirely by solar energy, so it can operate in pristine polar environments without adding to air pollution. The panels are mounted in an inverted V, allowing them to collect energy from the sun and sunlight reflected off the ice sheet.

A ground-penetrating radar powered by two rechargeable batteries rests on the back of the rover. The radar sends radio wave pulses into the ice sheet, and the waves bounce off buried features, informing researchers about the characteristics of the snow and ice layers.

From a research station operated by the National Science Foundation called Summit Camp, a spot where the ice sheet is about 2 miles thick, GROVER will crawl at an average speed of 1.2 mph (2 kilometers per hour). Because the sun never dips below the horizon during the Arctic summer, GROVER can work at any time during the day and should be able to work longer and gather more data than a human on a snowmobile.

A prototype of GROVER, minus its solar panels, was tested in January 2012 at a ski resort in Idaho. The laptop in the picture is for testing purposes only and is not mounted on the final prototype. Credit: Gabriel Trisca, Boise State University

A prototype of GROVER, minus its solar panels, was tested in January 2012 at a ski resort in Idaho. The laptop in the picture is for testing purposes only and is not mounted on the final prototype. Credit: Gabriel Trisca, Boise State UniversityAt the beginning of the summit tests, Koenig's team will keep GROVER close to camp and communicate with it via Wi-Fi within a three-mile (4.8-kilometer) range. GROVER will transmit snippets of data during the trial to ensure it is working properly but the majority of data will be recovered at the end of the season. The researchers eventually will switch to satellite communications, which will allow the robot to roam farther and transmit data in real time. Ideally, researchers will be able to drive the rover from their desks.

"We think it's really powerful," said Gabriel Trisca, a Boise State master's degree student who developed GROVER's software. "The fact is the robot could be anywhere in the world and we'll be able to control it from anywhere."

Michael Comberiate, a retired NASA engineer and manager of Goddard's Engineering Boot Camp said the Earth-bound Greenland Rover is similar to NASA missions off the planet.

"GROVER is just like a spacecraft but it has to operate on the ground," Comberiate said. "It has to survive unattended for months in a hostile environment, with just a few commands to interrogate it and find out its status and give it some directions for how to accommodate situations it finds itself in."

Koenig hopes more radar data will help shed light on Greenland's snow accumulation. Scientists compare annual accumulation to the volume of ice lost to sea each year to calculate the ice sheet's overall mass balance and its contribution to sea level rise.