News | April 24, 2013

Getting past 'I'm smart, you're stupid'

Often I hear positive descriptions of science: “It’s creative, fun, open, and interesting,” muddled with tired, old stereotypes: “Science is sterile, movies portray scientists as loners lacking social skills, it’s too complicated, I’m just not good at science.”

In the last few years, there has been an upsurge of websites, outreach opportunities, new media products and treatises about ways to improve public perception and public engagement in science. Nevertheless, the relationship between the public and the scientific community remains estranged. Scientific and academic communities have the habit of focusing inward, seeking engagement from those who are already engaged, while overlooking a portion of the public that feels cut off.

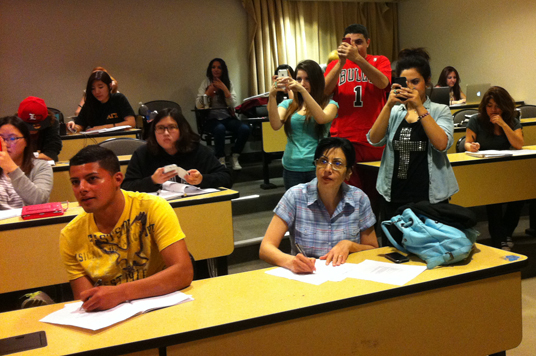

Professors are still in the outdated habit of failing half the class as a protocol to promote rigor, and our scientific community is made up of those who found a way to conform in this atmosphere. Failed students don’t merely vanish: they become our neighbors, our fellow citizens. They influence society. As a community of scientists and science educators, are they failing us or are we the ones who are failing them? Are we closing the door to people who may bring something creative, are we locking ourselves in?

Science-themed videos land in my inbox daily, tagged with notes like “this is great” on products that are boring or unmemorable and have few clicks. It’s not enough for us to pat ourselves on the back for our excellent work; it’s the public that ultimately judges the quality of our products. If you’re presenting a talk and you look at the faces of your audience and their eyes are glazed or they’re texting, then your talk is boring. If your online product isn’t getting thousands of hits then you need to re-evaluate and make changes. You will know if your message resonates in a meaningful way if you get invited back, referred, liked, shared, and remembered.

We need to maintain the rigorous content of scientific principles while at the same time engage a broader audience so that the scientific message resonates in a more meaningful way for more people. Having a Ph.D. and doing research is one way to participate in science, but not the only way. Yes, our students and our public must raise the bar on their intellectual capacity, and who wouldn’t want to participate in expanding their brainpower? But it’s us—the scientists, communicators, and educators—who also need to raise our own standards and expand our own capacity to find a way to connect.

Thank you for your comments.

Laura