News | April 7, 2013

Severe thunderstorms and climate change

Though thunderstorms are familiar and seemingly non-threatening, severe thunderstorms can lead to dangerous supercells, derechos, and tornadoes.

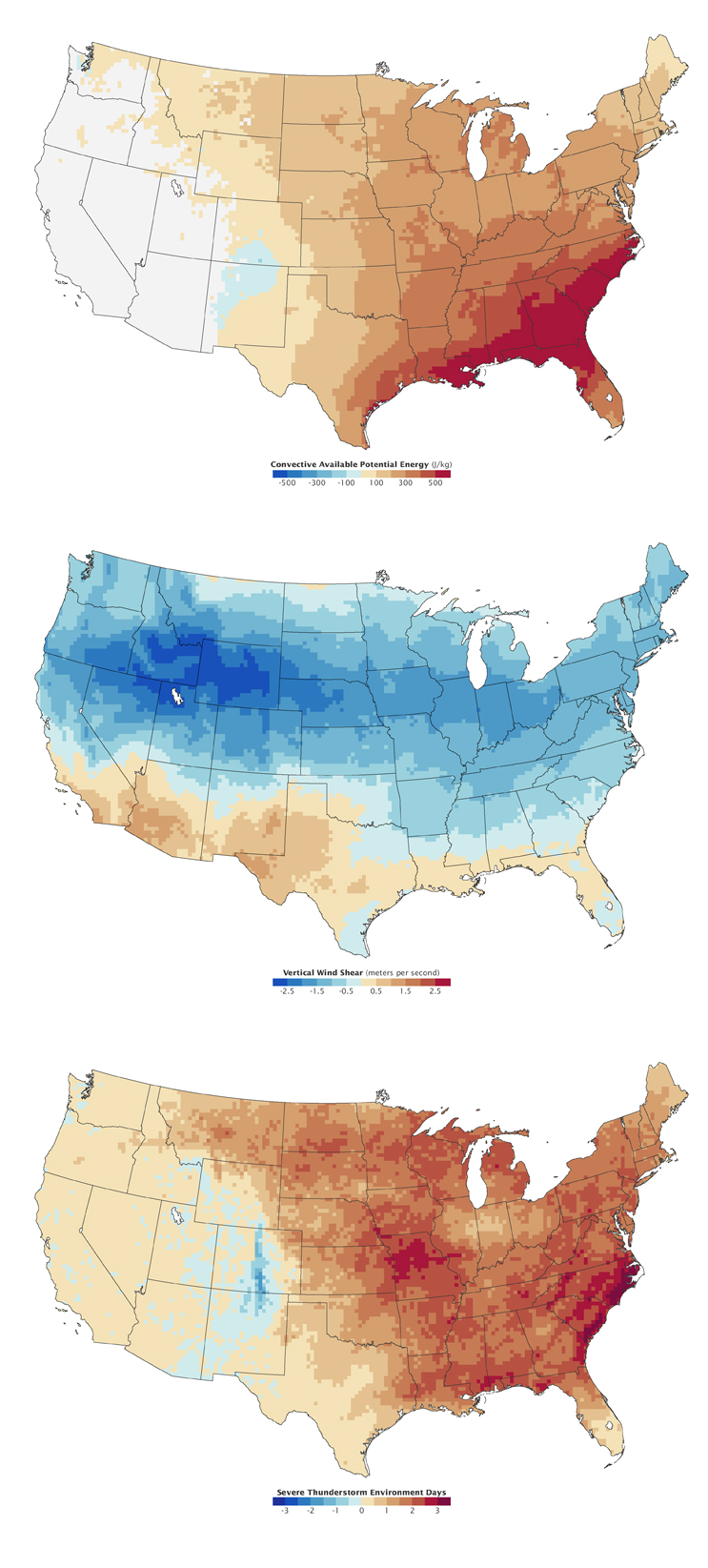

Severe thunderstorms are defined as having sustained winds above 93 kilometers (58 miles) per hour or unusually large hail, and there are two key factors that fuel their formation: convective available potential energy (CAPE) and strong wind shear. CAPE is a measure of how much raw energy is available for storms; it relates to how warm, moist, and buoyant air is in a given area. Wind shear is a measure of how the speed and direction of winds change with altitude.

“CAPE can provide storms with the raw fuel to produce rain and hail, and vertical wind shear can pull and twist weak storms into strong, windy ones,” explained Harold Brooks, a meteorologist at NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory.

Scientists have evidence that global warming should increase CAPE by warming the surface and putting more moisture in the air through evaporation. On the other hand, disproportionate warming in the Arctic should lead to less wind shear in mid-latitude areas prone to severe thunderstorms. So one factor makes severe storms more likely, while the other makes them less so.

Researchers have developed detailed climate models (results shown above) that aim to distinguish which of these opposing effects will dominate as the climate changes. One study, led by Robert Trapp of Purdue University, found that a doubling of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere would significantly increase the number of days that severe thunderstorms could occur in the southern and eastern United States. Cities such as Atlanta and New York could see a doubling of the number of days that severe thunderstorms could occur.

The maps above show the results of a model comparing the summer climate in 2072–2099 with the climate from 1962–1989. CAPE (top map) is predicted to rise enough to overwhelm a slight decrease in vertical wind shear (middle map), leading to an increase in severe thunderstorms (third map), especially in Missouri and coastal North and South Carolina. The modeling suggests that the increase in CAPE will be the strongest in the Southeast and the decrease in wind shear strongest in the Mountain West. The eastern United States will see more of an increase in days favorable to severe thunderstorm formation than the western part of the country.

Read our feature In a Warming World, Storms May Be Fewer but Stronger to learn more about climate change and storms.

References

- Brooks, H. (2013, April 1) Severe thunderstorms and climate change. Atmospheric Research, 123, 129-138.

- Del Genio, A. et al (2007, August 17) Will moist convection be stronger in a warmer climate? Geophysical Research Letters, 34 (16), 16703.

- NOAA Severe Weather 101:Tornado Basics. Accessed March 1, 2013.

- Trapp, R. et al (2007, December 4) Changes in severe thunderstorm environment frequency during the 21st century caused by anthropogenically enhanced global radiative forcing. PNAS, 104 (50), 19719-19723.