News | September 26, 2010

A symptom of climate change

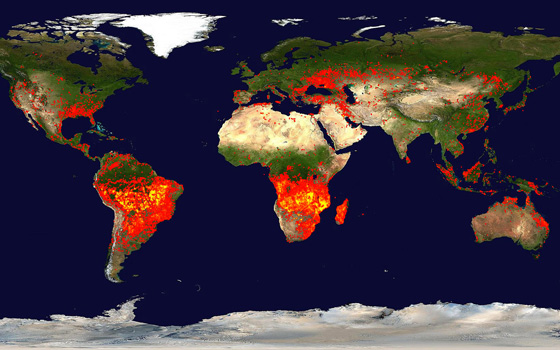

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra satellite shows fires around the world. Credit: NASA

This summer, wildfires swept across some 22 regions of Russia, blanketing the country with dense smoke and in some cases destroying entire villages. In the foothills of Boulder, Colo., this month, wildfires exacted a similar toll on a smaller scale.

That's just the tip of the iceberg. Thousands of wildfires large and small are under way at any given time across the globe. Beyond the obvious immediate health effects, this "biomass" burning is part of the equation for global warming. In northern latitudes, wildfires actually are a symptom of the Earth's warming.

'We already see the initial signs of climate change, and fires are part of it," said Dr. Amber Soja, a biomass burning expert at the National Institute of Aerospace (NIA) in Hampton, Va.

And research suggests that a hotter Earth resulting from global warming will lead to more frequent and larger fires.

The fires release "particulates" -- tiny particles that become airborne -- and greenhouse gases that warm the planet.

Human ignition

A common perception is that most wildfires are caused by acts of nature, such as lightning. The inverse is true, said Dr. Joel Levine, a biomass burning expert at NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Va.

"What we found is that 90 percent of biomass burning is human instigated," said Levine, who was the principal investigator for a NASA biomass burning program that ran from 1985 to 1999.

Levine and others in the Langley-led Biomass Burning Program travelled to wildfires in Canada, California, Russia, South African, Mexico and the wetlands of NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Biomass burning accounts for the annual production of some 30 percent of atmospheric carbon dioxide, a leading cause of global warming, Levine said.

Dr. Paul F. Crutzen, a pioneer of biomass burning, was the first to document the gases produced by wildfires in addition to carbon dioxide.

"Modern global estimates agree rather well with the initial values," said Crutzen, who shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995 with Mario J. Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland for their "work in atmospheric chemistry, particularly concerning the formation and decomposition of ozone."

Northern exposure

Whether biomass burning is on the rise globally is not clear. But it definitely is increasing in far northern latitudes, in "boreal" forests comprised largely of coniferous trees and peatlands.

The reason is that, unlike the tropics, northern latitudes are warming, and experiencing less precipitation, making them more susceptible to fire. Coniferous trees shed needles, which are stored in deep organic layers over time, providing abundant fuel for fires, said Soja, whose work at the NIA supports NASA.

"That's one of the reasons northern latitudes are so important," she said, "and the smoldering peat causes horrible air quality that can affect human health and result in death."

Fires in different ecosystems burn at different temperatures due to the nature and structure of the biomass and its moisture content. Burning biomass varies from very thin, dry grasses in savannahs to the very dense and massive, moister trees of the boreal, temperate and tropical forests.

Fire combustion products vary over a range depending on the degree of combustion, said Levine, who authored a chapter on biomass burning for a book titled "Methane and Climate Change," published in August by Earthscan.

Flaming combustion like the kind in thin, small, dry grasses in savannahs results in near-complete combustion and produces mostly carbon dioxide. Smoldering combustion in moist, larger fuels like those in forest and peatlands results in incomplete combustion and dirtier emission products such as carbon monoxide.

Boreal fires burn the hottest and contribute more pollutants per unit area burned.

'Eerie experience'

Being near large wildfires is a unique experience, said Levine. "The smoke is so thick it looks like twilight. It blocks out the sun. It looks like another planet. It's a very eerie experience."

In Russia, the wildfires are believed caused by a warming climate that made the current summer the hottest on record. The hotter weather increases the incidence of lightning, the major cause of naturally occurring biomass burning.

Soja said she hopes the wildfires in Russia prompt the country to support efforts to mitigate climate change. In fact, Russia's president, Dmitri A. Medvedev, last month acknowledged the need to do something about it.

"What's happening with the planet's climate right now needs to be a wake-up call to all of us, meaning all heads of state, all heads of social organizations, in order to take a more energetic approach to countering the global changes to the climate," said Medvedev, in contrast to Russia's long-standing position that human-induced climate change is not occurring.

Michael Finneran/NASA Langley Research Center