Land ecosystems currently play a key role in mitigating climate change. The more carbon dioxide (CO2) plants and trees absorb during photosynthesis, the process they use to make food, the less CO2 remains trapped in the atmosphere, where it can cause temperatures to rise. But scientists have identified an unsettling trend – as levels of CO2 in the atmosphere increase, 86% of land ecosystems globally are becoming progressively less efficient at absorbing it.

Because CO2 is a main "ingredient" that plants need to grow, elevated concentrations of it cause an increase in photosynthesis, and consequently, plant growth – a phenomenon aptly referred to as the CO2 fertilization effect, or CFE. CFE is considered a key factor in the response of vegetation to rising atmospheric CO2 as well as an important mechanism for removing this potent greenhouse gas from our atmosphere – but that may be changing.

For a new study published Dec. 10 in Science, researchers analyzed multiple field, satellite-derived and model-based datasets to better understand what effect increasing levels of CO2 may be having on CFE. Their findings have important implications for the role plants can be expected to play in offsetting climate change in the years to come.

“In this study, by analyzing the best available long-term data from remote sensing and state-of-the-art land-surface models, we have found that since 1982, the global average CFE has decreased steadily from 21% to 12% per 100 ppm of CO2 in the atmosphere,” said Ben Poulter, study co-author and scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “In other words, terrestrial ecosystems are becoming less reliable as a temporary climate change mitigator.”

What’s Causing It?

Without this feedback between photosynthesis and elevated atmospheric CO2, Poulter said we would have seen climate change occurring at a much more rapid rate. But scientists have been concerned about how long the CO2 Fertilization Effect could be sustained before other limitations on plant growth kick in.

For instance, while an abundance of CO2 won’t limit growth, a lack of water, nutrients, or sunlight – the other necessary components of photosynthesis — will. To determine why the CFE has been decreasing, the study team took the availability of these other elements into account.

“According to our data, what appears to be happening is that there’s both a moisture limitation as well as a nutrient limitation coming into play,” Poulter said. “In the tropics, there’s often just not enough nitrogen or phosphorus, to sustain photosynthesis, and in the high-latitude temperate and boreal regions, soil moisture is now more limiting than air temperature because of recent warming.”

In effect, climate change is weakening plants’ ability to mitigate further climate change over large areas of the planet.

Next Steps

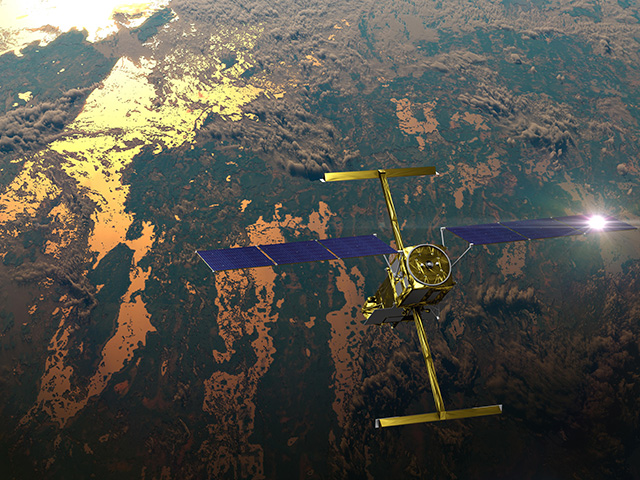

The international science team found that when remote-sensing observations were taken into account – including vegetation index data from NASA's Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) and the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments – the decline in CFE is more substantial than current land-surface models have shown. Poulter says this is because modelers have struggled to account for nutrient feedbacks and soil moisture limitations – due, in part, to a lack of global observations of them.

“By combining decades of remote sensing data like we have done here, we’re able to see these limitations on plant growth. As such, the study shows a clear way forward for model development, especially with new remote sensing observations of vegetation traits expected in coming years,” he said. “These observations will help advance models to incorporate ecosystem processes, climate and CO2 feedbacks more realistically.”

The results of the study also highlight the importance of the role of ecosystems in the global carbon cycle. According to Poulter, going forward, the decreasing carbon-uptake efficiency of land ecosystems means we may see the amount of CO2 remaining in the atmosphere after fossil fuel burning and deforestation start to increase, shrinking the remaining carbon budget.

“What this means is that to avoid 1.5 or 2 °C warming and the associated climate impacts, we need to adjust the remaining carbon budget to account for the weakening of the plant CO2 Fertilization Effect,” he said. “And because of this weakening, land ecosystems will not be as reliable for climate mitigation in the coming decades.”