Greenland and coastal Louisiana may not seem to have a lot in common. An autonomous territory of Denmark, Greenland is covered in snow most of the year and is home to about 56,000 people. On the other hand, more than 2 million people call coastal Louisiana home and the region rarely sees snow.

But their economies, though 3,400 miles (5,400 kilometers) apart, share a dependence on the sea. The majority of Greenland's residents rely on the territory's robust Arctic fishing industry. And in Louisiana, the coasts, ports and wetlands provide the basis for everything from shipping to fishing to tourism. As a result, both locales and the people who live in them are linked by a common environmental thread: melting ice and consequent sea level rise.

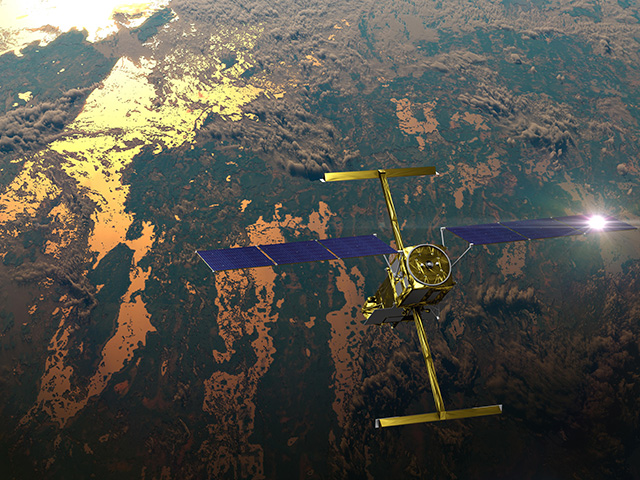

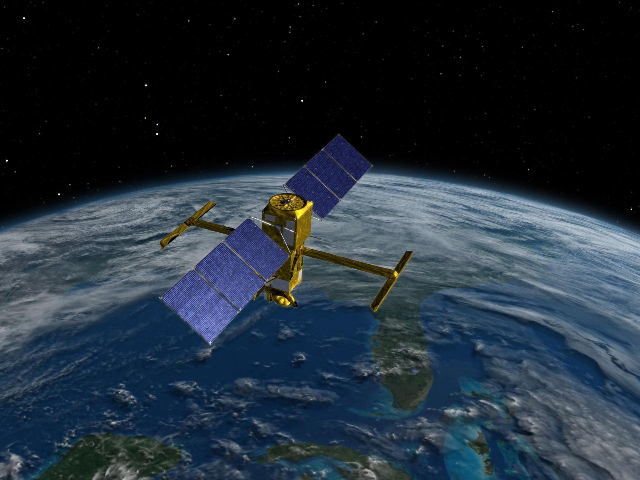

NASA satellites are keeping an eye on both.

NASA Sees the Seas

Thanks to altimetry missions, beginning with the U.S.-French TOPEX / Poseidon mission launched in 1992 and continuing through the present with the Jason series, we now have a nearly three-decade-long record of sea level change.

Similarly, because of missions like the U.S.-German Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) and its successor, GRACE Follow-On, we know a lot more about what the ice is doing than we used to, especially at the poles. For instance, we know that Greenland lost 600 billion tons of ice last summer alone. That's enough to raise global sea levels by a tenth of an inch (2.2 millimeters). We also know that both Greenland and Antarctica are losing ice six times faster than they were in the 1990s.

These numbers matter because frozen within all of the glaciers and ice sheets is enough water to raise global sea levels by more than 195 feet (60 meters)—key word here being "global." Ice that melts in Greenland and Antarctica, for example, increases the volume of water in the ocean as a whole and can lead to flooding far from where the melting occurred, like in coastal communities half a world away.

In addition to using satellite data to monitor sea levels and ice melt, NASA scientists are observing the seas from a closer vantage point.

"The satellites tell us it's happening. But we want to know why—what's causing it?" said Josh Willis of the agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. "Generally speaking, it's global warming. But in a specific sense, how much is it the melting of polar ice sheets as opposed to glaciers? And how much is it ocean warming and thermal expansion?" he said, referring to how water expands as it warms. "Most importantly, what's going to happen in the future?"

Willis is the principal investigator for NASA's Ocean's Melting Greenland (OMG), an air and ship-borne mission designed to answer some of these questions. OMG maps and measures the height of glaciers along Greenland's coast each year. It also measures the temperature and salinity of the ocean around the coastline and has developed precision maps of the ocean floor there. Combined, these datasets reveal to scientists how Greenland's glaciers are responding to changes both in the warming waters below them and in the warming air above them.

"The satellites are telling us how much global sea level is rising, but the airborne and shipborne data are really telling us how much Greenland is contributing to it, and what's causing Greenland to contribute to it," Willis said. "It's a piece of a much bigger puzzle, but it's an important piece because Greenland alone has enough ice to raise global sea levels by 25 feet [7.6 meters]."

Melting Here, Flooding There

As the ice melts in one part of the world, elsewhere, coastal communities in particular wrangle with the consequences—the most common: flooding. High-tide flooding, where seawater spills onto land and into low-lying communities when the tide comes in, has doubled in the last 30 years. Other factors, such as ocean currents, the terrain and subsidence, or land sinking, also influence a region's susceptibility to flooding.

In addition to measuring global sea level changes, NASA scientists are working with land and resource managers to help them understand and mitigate these regional flooding risks.

"A lot of coastal communities are working to identify particular parts of their towns where there have been flooding issues, and they are trying to adopt strategies to lessen the impact of sea level rise and flooding in those areas," said JPL's Ben Hamlington, head of the Sea Level Change Science Team. "We're often able to provide the high-resolution information that they need to make important decisions, particularly in terms of subsidence, which can differ quite a bit over even short distances."

Because subsidence is so variable—it can occur in measurements of less than an inch to feet, and over areas of a few acres to many miles—it is an important factor in assessing and responding to flood risk. For example, in a 2017 study of Hampton Roads, Virginia, an area prone to flooding, NASA scientists, including Hamlington (who was with Old Dominion University at the time), detected major differences in the rate of subsidence in areas just a few miles apart.

"It highlights the fact that subsidence information should be incorporated into land use decisions and taken into consideration for future planning, including at the local level," Hamlington said.

In order to get crucial information like this into the hands of stakeholders, Hamlington's team is working on a new, interactive sea level assessment tool. Available in coming weeks on the agency's sea level website, it will provide quantitative information, based on NASA observations, on sea level rise in the coastal U.S. and the processes driving it.

Disaster Response

One reason floods are among the most common natural disasters in the U.S., resulting in billions of dollars in damage each year, is that they can be caused by a number of factors, including excessive rainfall, snowmelt, levee or dam failures, or storm surges from hurricanes. In other words, flooding is a threat that effects nearly every region of the U.S.

NASA's role continues even after a flood has occurred. The agency regularly provides relief groups and response agencies, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), with crucial satellite-derived data and decision-support maps when flooding events occur.

"It can be difficult to assess the extent of flooding from the ground because flood waters can recede and flood extent can disappear in a matter of hours," said JPL's Sang-Ho Yun, Disaster Response lead on NASA's Advanced Rapid Imaging and Analysis (ARIA) team. "After an earthquake, damaged buildings stay damaged until they are repaired. But flood extent is like a ghost—it is there and then it disappears."

Earth-observing satellites can fill in some of the blanks. Using synthetic aperture radar (SAR) that penetrates clouds and rain, day and night, including data acquired by the European Space Agency's Sentinel-1 and Japan's ALOS-2 satellites, Yun and the ARIA team can identify areas that are likely flooded.

"In the satellite radar data, the bare ground has its own roughness, but when you cover the ground with smooth water, it becomes like a mirror," Yun said. "When the radar signal from the satellite hits the bare ground, it reflects back to the satellite. But when the signal hits water on the surface instead, it actually reflects away from the satellite, so flooded areas appear darker than normal."

Yun's team processes the satellite data to produce flood maps (like this one) that FEMA and other agencies can use in their disaster response efforts.

NASA's Disasters Program, in the agency's Earth Science Division, also provides extremely useful information on the use of Earth observations in the prediction of, preparation for, response to and recovery from natural disasters like flooding. The NASA Disasters Mapping Portal provides access to near real-time data products and maps of disaster areas. The flood dashboard, which brings together observations and products from NASA, the National Weather Service and the United States Geological Survey (USGS) to provide a more complete picture of the extent of flooding, is also publicly accessible.

In some way or other, the effects of sea level rise, whether direct or indirect, will touch us all. But from Greenland to Louisiana to coastal regions around the world, NASA continues to provide key insight into our rising seas and how to navigate the effects of sea level rise.

News Media Contact

Jane J. Lee

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-0307

jane.j.lee@jpl.nasa.gov