4 min read

› Larger view

Although drought and overgrown forests are often blamed for major fires in the western United States, new research using unique NASA before-and-after data from a megafire site indicates that highly localized winds sometimes play a much larger role -- creating large, destructive fires even when regional winds are weak.

The study was led by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado. It focused on the 2014 King Fire, using data from airborne instruments managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, with advanced computer simulations from NCAR. The King Fire occurred in the Sierra Nevada mountain range during California's severe multi-year drought and burned more than 97,000 acres (39,000 hectares).

The study team found that winds -- both very localized winds related to topography and winds created by the searing heat of the flames -- were the reason the fire suddenly ran 15 miles (24 kilometers) up a steep canyon one afternoon. Winds like these, sometimes only a few hundred yards (meters) across, often go undetected by weather stations that may be several miles away. In fact, for several days before the fire, nearby weather stations measured only weak winds.

"This brings into question several widely held and largely unquestioned assumptions, such as very large fires being caused by the accumulation of vegetation, persistent dry conditions, or requiring extreme conditions," said NCAR scientist Janice Coen, the lead author of the study. In the King Fire, she pointed out, "Small-scale winds and winds generated by the fire had a much greater impact on this fire, and potentially others like it, than any of the other factors."

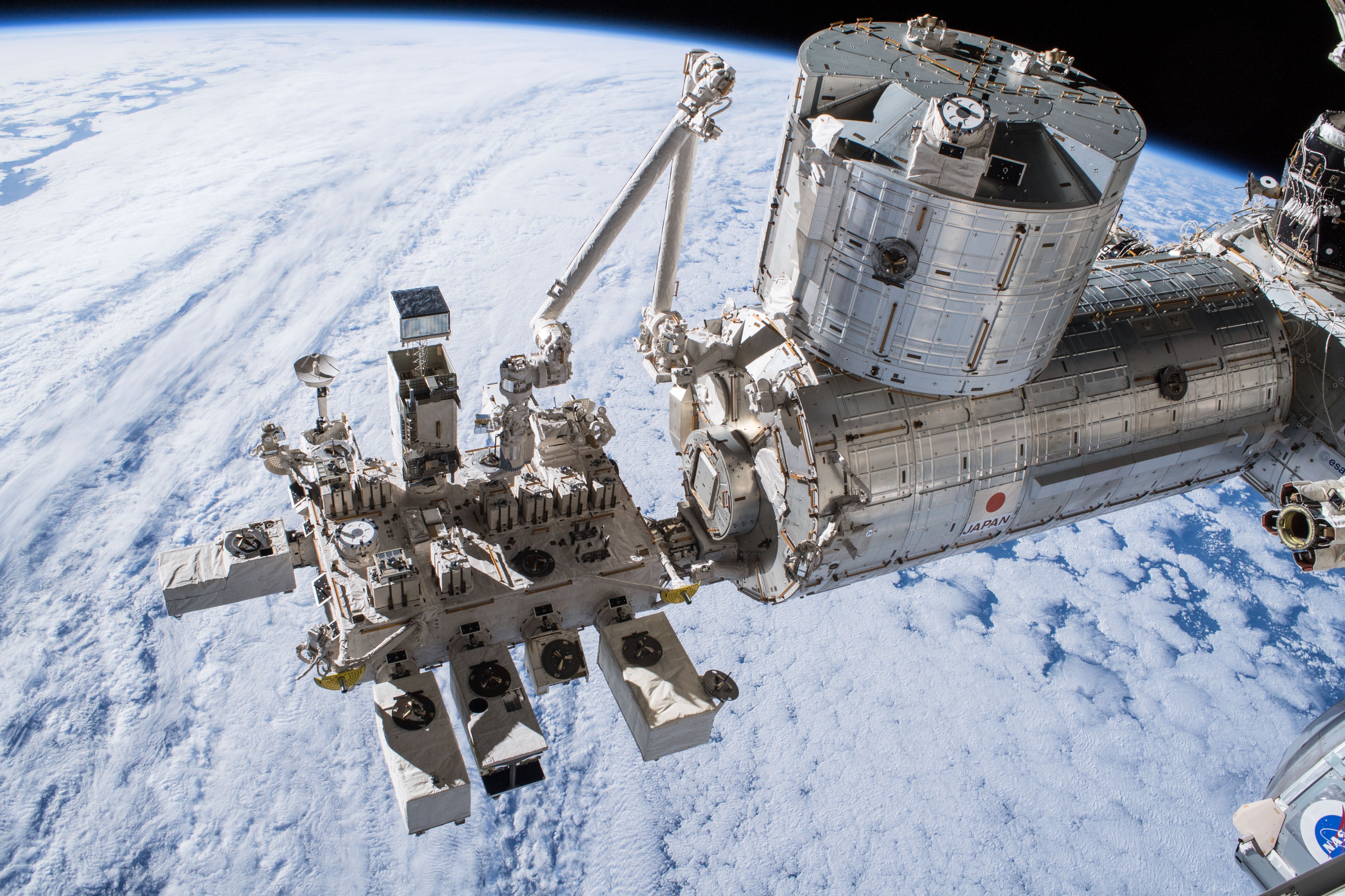

JPL scientist Natasha Stavros, a coauthor on the study, said, "The NASA airborne measurements were unique in that we observed the forest's vertical structure before and after a fire. These observations let us better identify the type of fuel -- grass, shrubs, or trees. That improved the model simulations, particularly of how the fire spread in areas where previous fires had burned or timber had been as harvested, and in areas where the burn severity was greatest."

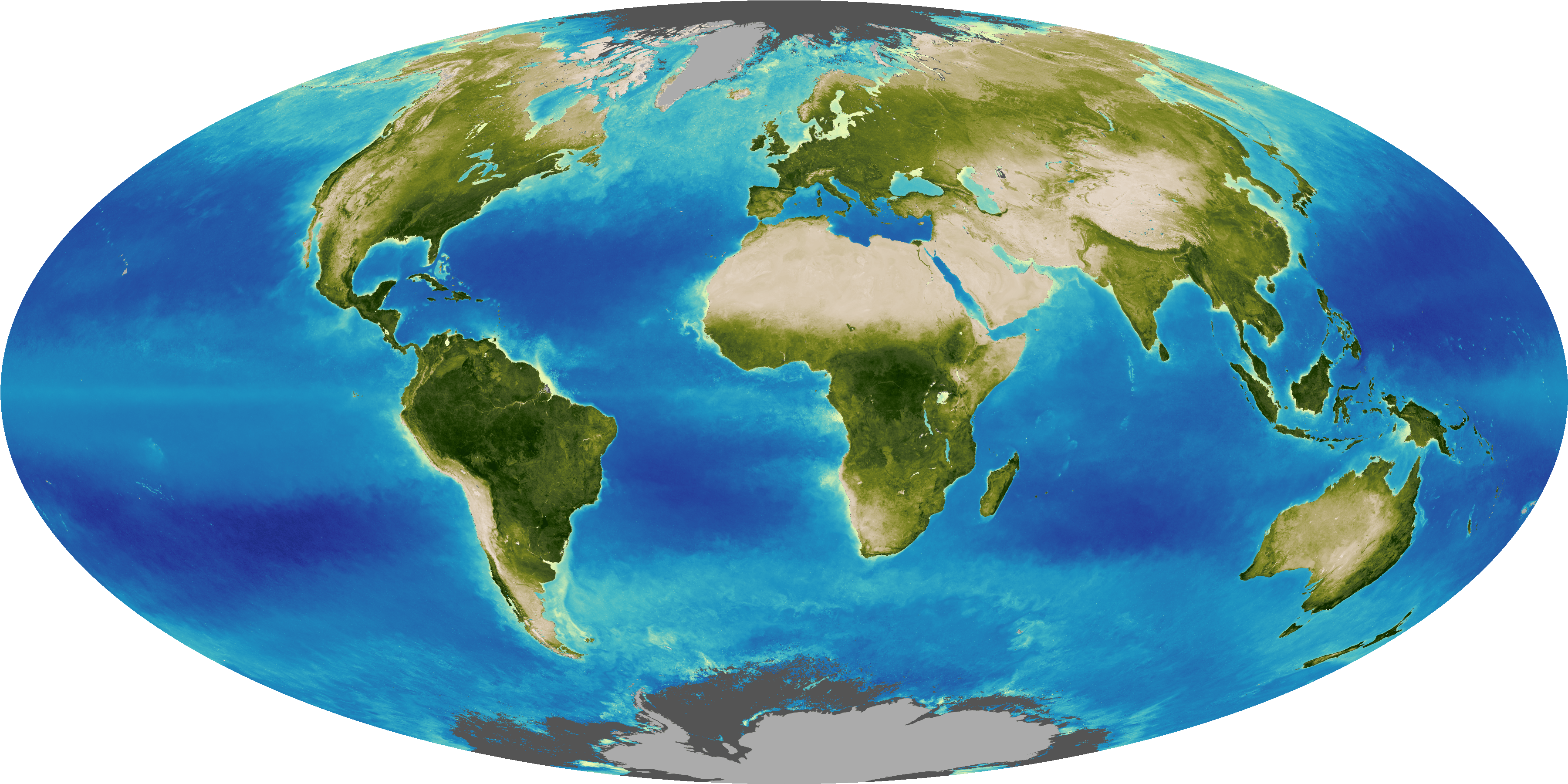

Large and destructive megafires are becoming more frequent in the western United States. Experts have attributed this to a changing climate, which is causing hotter and sometimes drier conditions, or to a century of fire suppression policies that have left forests with more vegetation to fuel the flames than in the past. Scientists cannot experiment with large and destructive wildfires, so they have fallen back on examining statistical correlations to try to tease out the key factors associated with megafires.

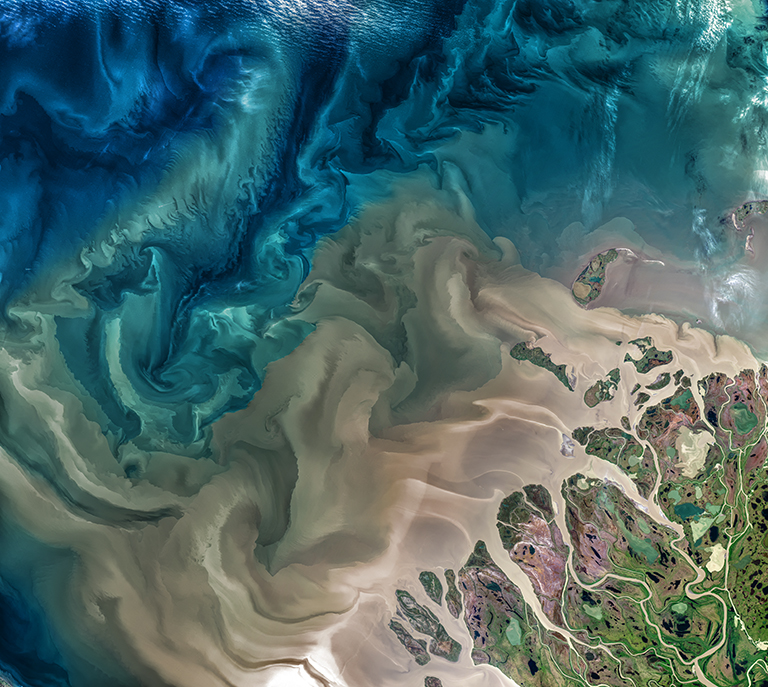

The area consumed by the King Fire, however, had been previously mapped by JPL's Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (AVIRIS) and MODIS/ASTER Airborne Simulator (MASTER) instruments in visible and thermal infrared wavelengths, as well as by a U.S. Forest Service lidar instrument, resulting in an extensive database about the forest structure and vegetation types. In addition, the authors had access to airborne thermal imagery collected during the fire. The detailed data gave them a rare opportunity to recreate an actual wildfire within a sophisticated NCAR computer model that combines weather prediction and fire behavior, testing the importance of different factors.

Simulations of the King Fire under more extreme drought conditions did not change the ultimate extent of the fire or greatly alter its expansion, and simulations with half of the actual fuel load (as might exist in a less overgrown forest) unfolded in about the same way as the real fire did.

The scientists concluded that the fire became stronger in the canyon because of the inclined slopes. Drought conditions or increased vegetation did help the fire to generate the strong updraft that drew flames up the canyon slope. These factors had little impact while the fire was on flatter ground.

"This is just one case, but it illustrates how the causes of a megafire have sometimes been misunderstood," Coen said.

The study, titled "Deconstructing the King Megafire," was published in the journal Ecological Applications. The research was funded by NASA.

For more information, see: