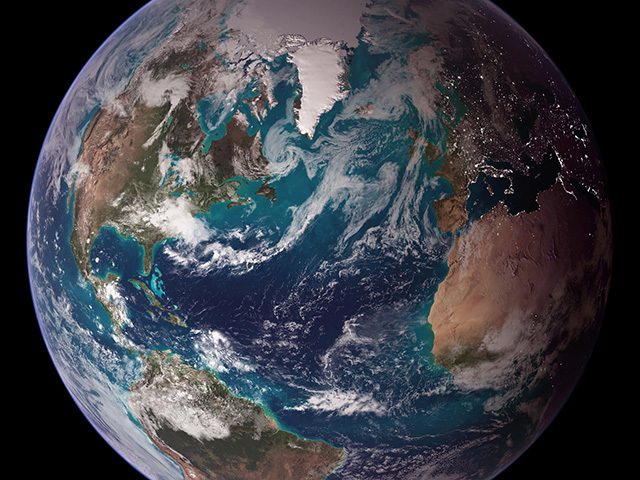

Google recently unveiled a new feature, “Waterways from Earth,” on Google Earth. The program relies on NASA and NOAA images to show our dynamic planet’s waterways from space. Here’s more about the science and stories behind those images.

Fluid dynamics on full display

Remote Rupert Bay in northern Quebec is a place where the majesty and dynamism of fluid dynamics is on display. With several rivers pouring into this nook of James Bay, the collision of river and seawater combines with the churn of tides and the motion of currents to make swirls of colorful fluid that could impress even the most jaded of baristas.

Read the full story on Earth Observatory.

After islands sink, coral remains

NASA’s Earth Observing-1 satellite captured this natural-color image of South Keeling Islands in 2009. Coral atolls – which are largely composed of huge colonies of tiny animals such as cnidaria – form around islands. After the islands sink, the coral remains, generally forming complete or partial rings. Only some parts of South Keeling Islands still stand above the water surface. In the north, the ocean overtops the coral.

Read the full story on Earth Observatory.

Storm stirs sediment

Category 3 Hurricane Gonzalo passed over Bermuda in 2014, stirring up sediment in the shallow bays and lagoons around the island and spreading a huge mass of sediment across the North Atlantic Ocean.

Stores of calcium carbonate sediments are moved from the shallows to the deep ocean by storms or density flows.

Storm-induced export of carbonate sediments into the deep ocean—where they mostly dissolve—is a significant process in the ocean’s carbonate and carbon cycles. It's also important for the eventual neutralization of excess carbon dioxide entering the oceans because of increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations from fossil fuel combustion.

Read the full story on Earth Observatory.

The Gulf Stream in infrared

The Gulf Stream is an important part of the global ocean conveyor belt that moves water and heat across the North Atlantic from the equator toward the poles. Stretching from tropical Florida to the doorstep of Europe, this river of water carries a lot of heat, salt and history. It is one of the strongest currents on Earth, and one of the most studied.

This image shows a small portion of the Gulf Stream about 300 miles (500 kilometers) east of Charleston, South Carolina, in infrared.

“Infrared bands measure how much energy is emitted by the surface of the Earth at particular wavelengths,” said Matthew Montanaro, a researcher on NASA’s Landsat team. “We can calculate the surface temperature from these measurements through math and some modeling. Essentially, the higher the infrared signal measured, the higher temperature on the surface.”

Read the full story on Earth Observatory.

British Columbia in bloom

In late August 2016, the waters off British Columbia, Canada, turned green with blooming phytoplankton, or plant-like organisms.

For reasons that scientists are still trying to figure out, the Strait of Georgia and nearby inlets were teeming with coccolithophores, a harmless type of phytoplankton. Coccolithophores have chalky, scale-like shells made of calcium carbonate. The milky-white color of those shells can brighten and discolor otherwise blue waters when the plankton explode in such massive blooms. Marine scientists believe some harmless species of diatoms are also in the mix, adding to the green color.

Read the full story on Earth Observatory.

‘Carpets’ of cyanobacteria

Large, dense blooms of cyanobacteria are seen in the Baltic in August, 2015. Cyanobacteria are an ancient type of marine bacteria that, like other phytoplankton, capture and store solar energy through photosynthesis. Some are toxic to humans and animals. Moreover, large blooms can cause an oxygen-depleted dead zone where other organisms cannot survive.

Satellite images alone cannot say definitively that this bloom contains cyanobacteria—analysis of ocean water samples would be required to confirm it. Blooms like this flourish in the Baltic Sea during summertime, when there is ample sunlight and high levels of nutrients.

During this bloom, Maren Voss of the Leibniz Institute of Baltic Sea Research, a phytoplankton and cyanobacteria expert, was in the area on a research cruise. She confirmed that the bloom contained a type of cyanobacteria called Nodularia. Writing in an email from the field, she noted: “We steamed through ‘carpets’ of it the entire day yesterday (Aug. 12, 2015) west of Gotland.”

Read the full story on Earth Observatory.

Waves beneath waves

This photograph, taken in 2013 from the International Space Station (ISS), shows the north coast of Trinidad and a series of subtle, interacting arcs in the southeastern Caribbean. These are known as “internal waves,” the surface manifestation of slow waves that move well beneath the surface. Internal waves produce enough of an effect on the sea surface to be seen from space, but only where they are enhanced due to sunglint, or reflection of sunlight, back toward the Space Station.

Read the full story on Earth Observatory.

Land of lakes

During the last Ice Age, nearly all of Canada was covered by massive ice sheets. Thousands of years later, the landscape of Nunavut Territory – “our land” in the Inuktitut language – still shows the scars. Surfaces that were scoured by retreating ice and then flooded by Arctic seas are now dotted with millions of lakes, ponds and streams.

This area is frequently referred to as "Barren Grounds" because the soil remains frozen for much of the year, limiting the growth of trees and agriculture. However, looking beyond the “visible” spectrum reveals details from space. This false-color image from our Terra satellite shows vegetation in red, showing that during the summer thaw there is plenty of plant life in the form of lichens, mosses, shrubs and grasses.

Read the full story on Earth Observatory.

Sediments settle on the seafloor

In the southernmost reaches of Myanmar, along the border with Thailand, lies the Mergui Archipelago. The archipelago in the Andaman Sea is made up of more than 800 islands surrounded by extensive coral reefs.

This natural color image acquired by Landsat 5 on Dec. 14, 2004, shows the middle portion of the archipelago, including Auckland and Whale Bays. Swirling patterns are visible in the near-shore waters as sediments carried by rivers slowly settle out and are deposited on the seafloor. The heavy sediment loads make the river appear nearly white. As those sediments settle out, the seawater appears deeper shades of blue. The tropical rainforests of the region appear deep green.

Read the full story on Earth Observatory. More:

A volcanic mix in Tanzania

Lake Natron in northern Tanzania is mostly inhospitable to life, except for a few species adapted to its warm, salty and alkaline water. Small pools can fill with blooms of haloarchaea – salt-loving microorganisms that impart the pink and red colors to the shallow water. Nearby volcanoes produce molten mixtures of sodium carbonate and calcium carbonate salts that move through faults and well up in more than 20 hot springs that ultimately empty into the lake.

Landsat 8 captured this natural-color images of Lake Natron and its surroundings. It shows the lake on March 6, 2017, very early in the rainy season that runs from March to May.

Read the full story on Earth Observatory.