Operation IceBridge is flying in Greenland to measure how much ice has melted over the course of the summer from the ice sheet. The flights, which began on Aug. 25 and will go on until Sept. 21, repeat paths flown this spring and aim to monitor seasonal changes in the elevation of the ice sheet.

“We started to mount these summer campaigns on a regular basis two years ago,” said Joe MacGregor, IceBridge’s deputy project scientist and a glaciologist with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “If the flights go as expected, the result will be a high-quality survey of some of the fastest melting areas in Greenland and across as much of the island as possible.”

The image above was taken during a research flight carried on Aug. 29 and shows the calving front—the end of the glacier, from where it sheds chunks of ice—of the Zachariae Isstrom glacier in northeast Greenland. During the first week of the end-of-summer campaign, IceBridge was based in Thule Air Base, in northwest Greenland. The melt season ends earlier in the north of the island, and IceBridge aimed to complete its northernmost flights before any significant snowfall had occurred there. From Thule, the campaign surveyed the northwest coast of Greenland and the fast-changing Zachariæ Isstrøm, Nioghalvfjerdsfjorden (79ºN) and Petermann glaciers.

“If the flights go as expected, the result will be a high-quality survey of some of the fastest melting areas in Greenland and across as much of the island as possible.”

On Sept. 1, the IceBridge team moved to Kangerlussuaq, in central western Greenland, from where they plan to fly over fast-changing areas such as Jakobshavn Isbræ and Helheim Glacier. The goal is to accomplish 16 flights in total during the campaign.

For this campaign, IceBridge is flying on a B200T King Air aircraft from Dynamic Aviation, a NASA contractor. The plane is carrying the Land, Vegetation and Ice Sensor, a laser instrument built by Goddard that measures changes in the ice elevation with an accuracy better than 4 inches (about 10 centimeters), and a high-resolution camera system to map the ice surface. The summer flights are about five and a quarter hours long, shorter than the 8-hour missions carried during IceBridge’s spring Arctic campaign, so the original paths flown have been straightened to better suit the elevation at which the B200T flies —about 28,000 feet (about 8,534 meters), much higher than that of the regular spring flights.

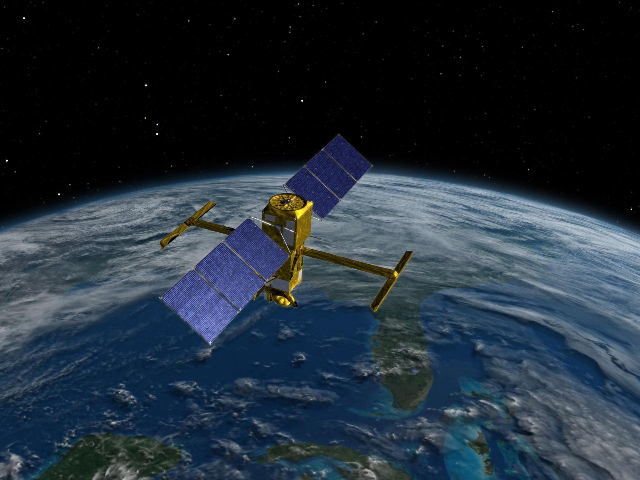

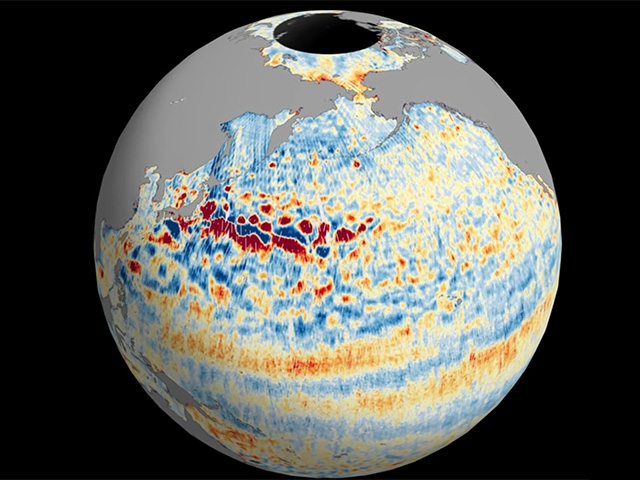

“For this campaign, we’re mapping as broad an area as possible, because we want to understand the seasonal cycle of elevation change across the entire ice sheet,” MacGregor said. “When NASA’s Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2) mission is up and running next year, it’ll be mapping these changes continuously. We need to better understand the magnitude of seasonal elevation change between the spring and the summer right now so that we have a starting point from which to evaluate any trend observed by ICESat-2.”

The mission of Operation IceBridge, NASA’s longest-running airborne survey to monitor polar ice, is to collect data on changing polar land and sea ice and maintain continuity of measurements between ICESat missions. The original ICESat mission launched in 2003 and ended in 2009, and its successor, ICESat-2, is scheduled for launch in late 2018. Operation IceBridge began in 2009 and is currently funded until 2019. The planned overlap with ICESat-2 will help scientists validate the satellite’s measurements.

For more about Operation IceBridge and to follow the current campaign, visit http://www.nasa.gov/icebridge.