News | October 26, 2016

Art turns public eyes (and ears) toward space

Visitors inside the Orbit Pavilion, a sound installation designed to teach the public about NASA’s earth science satellites. The installation was designed at JPL and opens to the public at The Huntington Library, Art Collections & Botanical Gardens on Oct. 29, 2016. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

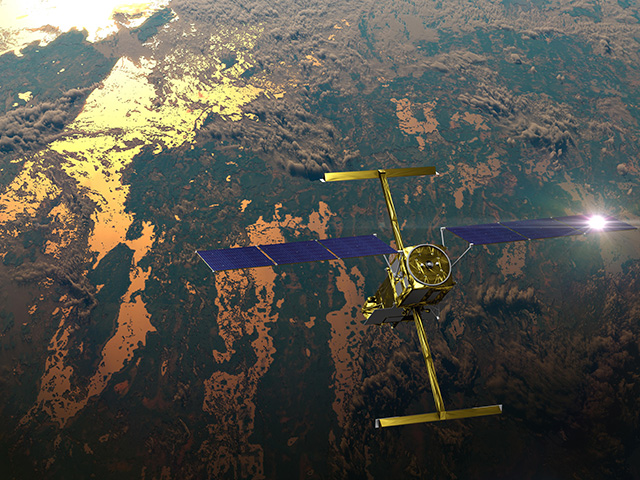

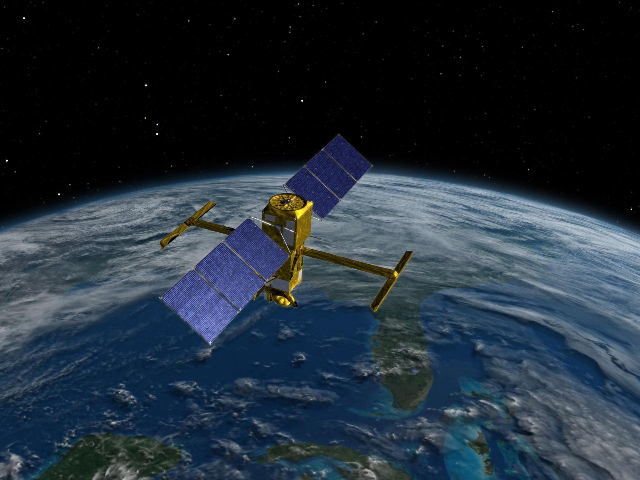

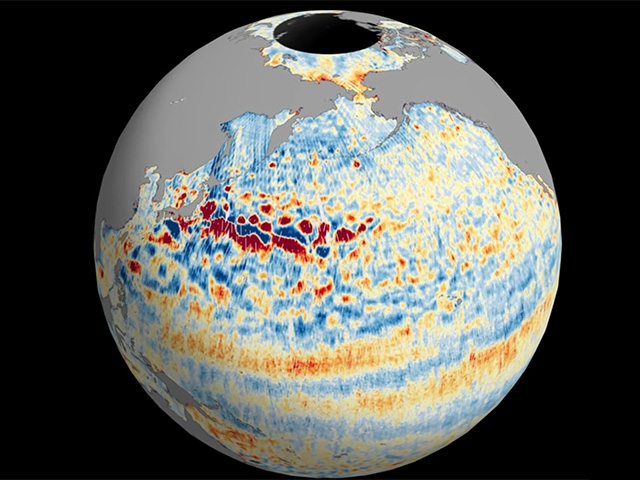

You might not realize it, but there’s a silent symphony overhead at any given time: NASA’s satellites talking to Earth. They track our planet’s weather, the height of its oceans, and even the changing mass of its ice. Those science measurements are then beamed down to ground stations, where they’re processed for scientists studying our changing world.

Starting this weekend, the public is invited to an educational experience where they can hear that space chatter for themselves. The Orbit Pavilion is a sound installation opening Saturday, Oct. 29, at The Huntington Library, Art Collections & Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. The installation lets listeners “hear” 19 of NASA’s Earth science satellites pass over them, providing a fun and engaging way to learn about space. It originally debuted in 2015 as part of New York’s World Science Festival.

From the outside, the installation looks like a giant, futuristic seashell; enter, and you can hear as satellites approach the horizon and sail overhead. Each satellite causes speakers to generate a simulated sound, ranging from desert winds to a crashing wave or rustling leaves. A digital screen identifies the individual satellites, providing an opportunity to learn how they contribute to NASA’s science missions.Orbit is the brainchild of The Studio at JPL, an art and design workshop that develops creative ways to educate the public on space exploration. Since 2003, the team has developed everything from expoplanet travel posters to digital light sculptures, all with the aim of increasing public awareness of space science.

The team collaborated with Jason Klimoski and Lesley Chang of Brooklyn-based architectural firm STUDIOKCA, who conceived of and designed Orbit’s seashell structure. They also collaborated with Shane Myrbeck, who composed Orbit’s soundscape and engineered the audio system.

“What we’re really interested in doing is making an experience where people can walk out and understand that these satellites move above them,” said David Delgado, a visual strategist at JPL. “We want them to feel the presence of those satellites and know exactly where they are in the sky -- to be able to hear them and point their finger at where they are.”

JPL visual strategist Dan Goods said Orbit’s concept can be traced back to around 2005 when he and Delgado visited one of the global antenna arrays that form NASA’s Deep Space Network. The dishes range from 112 to 230 feet (34 to 70 meters) wide, towering over the desert in Goldstone, California, an hour north of Barstow.

But what visitors to the Goldstone complex can’t see, Goods and Delgado realized, were the satellites talking to those antennas.

“Imagine being able to listen to those satellite locations,” Goods remembers thinking. He could visualize a space where that was possible, but it would require a 360-degree sound system.

Goods later met Myrbeck, a composer and sound artist who created exactly those kinds of systems for his company, Arup. Their technology is often used to simulate the acoustics of concert halls prior to construction.

Myrbeck composed sounds for each of the 19 satellites. When one of the satellites passes overhead, Orbit generates both naturalistic sounds and electronic, synthesized ones. The combined effect gives each satellite a distinctive soundscape that moves along the satellite’s trajectory.

“Our senses let us perceive everything we do,” Delgado said. “A lot of times, people talk about satellites, and we want to see them, but can’t. Could we allow people to use a different sense to understand where these satellites are? We liked the visceral experience of hearing things overhead.”

“A big hope for us is that people would leave the Orbit understanding that NASA studies the Earth,” Goods said. “If they get that, that’s great. But it’s also a starting point for their curiosity – a doorway to other questions.”

Media contact

Andrew Good

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-2433

andrew.c.good@jpl.nasa.gov