News | February 26, 2013

NASA's Aquarius sees salty shifts

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Editor's note: Click here to see real-time Aquarius images in our Eyes on the Earth interactive.

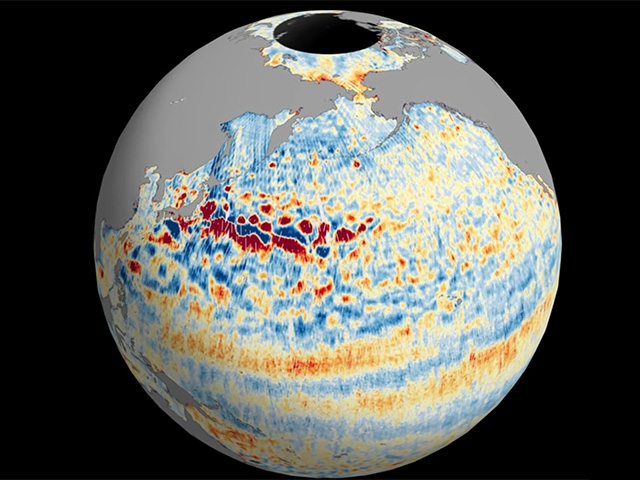

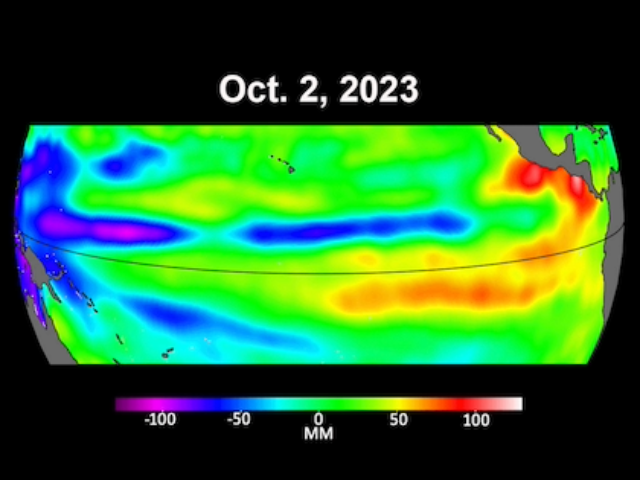

The colorful images chronicle the seasonal stirrings of our salty world: Pulses of freshwater gush from the Amazon River’s mouth; an invisible seam divides the salty Arabian Sea from the fresher waters of the Bay of Bengal; a large patch of freshwater appears in the eastern tropical Pacific in the winter. These and other changes in ocean salinity patterns are revealed by the first full year of surface salinity data captured by NASA’s Aquarius instrument.

“With a bit more than a year of data, we are seeing some surprising patterns, especially in the tropics,” said Aquarius Principal Investigator Gary Lagerloef, of Earth Space Research in Seattle. “We see features evolve rapidly over time.”

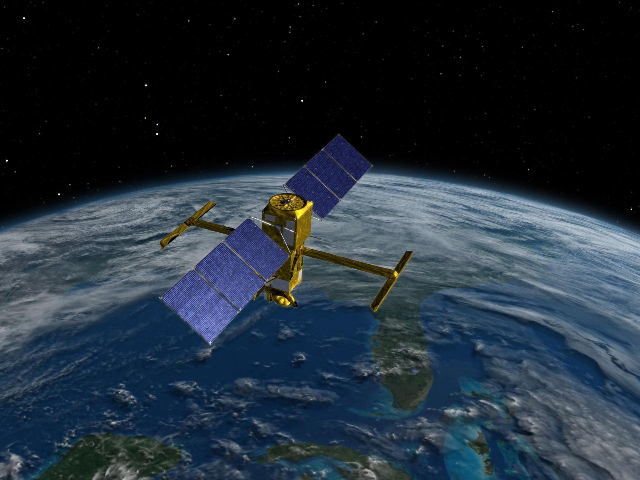

NASA’s Aquarius instrument has been orbiting the Earth for a year, measuring changes in salinity, or salt concentration, in the surface of the oceans. The Aquarius team released last September this first global map of ocean saltiness, a composite of the first two and a half weeks of data since the instrument became operational on August 25. Credit: NASA/GSFC/JPL-Caltech Watch an animation of how Aquarius works.

NASA’s Aquarius instrument has been orbiting the Earth for a year, measuring changes in salinity, or salt concentration, in the surface of the oceans. The Aquarius team released last September this first global map of ocean saltiness, a composite of the first two and a half weeks of data since the instrument became operational on August 25. Credit: NASA/GSFC/JPL-Caltech Watch an animation of how Aquarius works. The salinity sensor detects the microwave emissivity of the top 1 to 2 centimeters (about an inch) of ocean water – a physical property that varies depending on temperature and saltiness. The instrument collects data in 386 kilometer-wide (240-mile) swaths in an orbit designed to obtain a complete survey of global salinity of ice-free oceans every seven days.

The changing ocean

The animated version of Aquarius’ first year of data unveils a world of varying salinity patterns. The Arabian Sea, nestled up against the dry Middle East, appears much saltier than the neighboring Bay of Bengal, which gets showered by intense monsoon rains and receives freshwater discharges from the Ganges and other large rivers. Another mighty river, the Amazon, releases a large freshwater plume that heads east toward Africa or bends up north to the Caribbean, depending on the prevailing seasonal currents. Pools of freshwater carried by ocean currents from the central Pacific Ocean’s regions of heavy rainfall pile up next to Panama’s coast, while the Mediterranean Sea sticks out in the Aquarius maps as a very salty sea.

One of the features that stand out most clearly is a large patch of highly saline water across the North Atlantic. This area, the saltiest anywhere in the open ocean, is analogous to deserts on land, where little rainfall and a lot of evaporation occur. A NASA-funded expedition, the Salinity Processes in the Upper Ocean Regional Study (SPURS), traveled to the North Atlantic’s saltiest spot last fall to analyze the causes behind this high salt concentration and to validate Aquarius measurements.

“My conclusion after five weeks out at sea and analyzing five weekly maps of salinity from Aquarius while we were there was that indeed, the patterns of salinity variation seen from Aquarius and by the ship were similar,” said Eric Lindstrom, NASA’s physical oceanography program scientist, of NASA Headquarters, Washington, and a participant of the SPURS research cruise.

Future goals

A Delta II rocket carrying the international Aquarius/SAC-D observatory launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, on June 10, 2011. Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls Watch a video of Aquarius’ launch.

A Delta II rocket carrying the international Aquarius/SAC-D observatory launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, on June 10, 2011. Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls Watch a video of Aquarius’ launch.“The Aquarius prime mission is scheduled to run for three years but there is no reason to think that the instrument could not be able to provide valuable data for much longer than that,” said Gene Carl Feldman, Aquarius project manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “The instrument has been performing flawlessly and our colleagues in Argentina are doing a fantastic job running the spacecraft, providing us a nice, stable ride.”

In future years, one of the main goals of the Aquarius team is to figure out ways to fine-tune the readings and retrieve data closer to the coasts and the poles. Land and ice emit very bright microwave emissions that swamp the signal read by the satellite. At the poles, there’s the added complication that cold polar waters require very large changes in their salt concentration to modify their microwave signal.

Still, the Aquarius team was surprised by how close to the coast the instrument is already able to collect salinity measurements.

“The fact that we’re getting areas, particularly around islands in the Pacific, that are not obviously badly contaminated is pretty remarkable. It says that our ability to screen out land contamination seems to be working quite well,” Feldman said.

Another factor that affects salinity readings is intense rainfall. Heavy rain can affect salinity readings by attenuating the microwave signal Aquarius reads off the ocean surface as it travels through the soaked atmosphere. Rainfall can also create roughness and shallow pools of fresh water on the ocean surface. In the future, the Aquarius team wants to use another instrument aboard Aquarius/SAC-D, the Argentine-built Microwave Radiometer, to gauge the presence of intense rain simultaneously to salinity readings, so that scientists can flag data collected during heavy rainfall.

An ultimate goal is combining the Aquarius measurements to those of its European counterpart, the Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity satellite (SMOS) to produce more accurate and finer maps of ocean salinity. In addition, the Aquarius team, in collaboration with researchers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is about to release its first global soil moisture dataset, which will complement SMOS’ soil moisture measurements.

“The first year of the Aquarius mission has mostly been about understanding how the instruments and algorithms are performing,” Feldman said. “Now that we have overcome the major hurdles, we can really begin to focus on understanding what the data are telling us about how the ocean works, how it affects weather and climate, and what new insights we can gain by having these remarkable salinity measurements.”

Aquarius was built by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Goddard. JPL managed Aquarius through its commissioning phase and is archiving mission data. Goddard now manages Aquarius mission operations and processes science data. Argentina's space agency, Comisión Nacional de Actividades Espaciales (CONAE), provided the SAC-D spacecraft, optical camera, thermal camera with Canada, microwave radiometer, sensors from various Argentine institutions and the mission operations center. France and Italy also contributed instruments.