News | November 16, 2011

Ocean temperatures can predict Amazon fire season severity

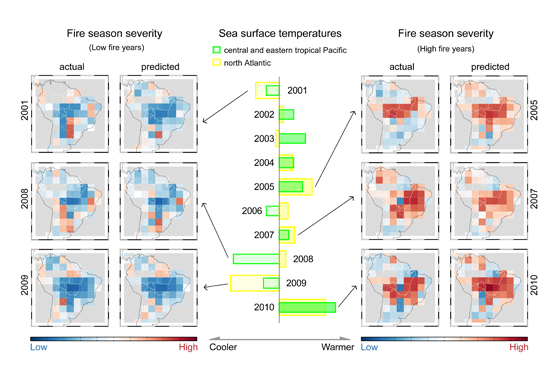

A new model uses sea surface temperatures to successfully predict fire activity in the Amazon months in advance. The diagram above shows the model predictions and a representation of the actual observations side by side. The high fire seasons of 2005, 2007 and 2010 are shown on the right of the diagram. The low fire seasons of 2001, 2008 and 2009 are shown on the left. Credit: UC Irvine/Yang Chen

By Patrick Lynch,

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

GREENBELT, Md. — By analyzing nearly a decade of satellite data, a team of scientists led by researchers from the University of California, Irvine and funded by NASA has created a model that can successfully predict the severity and geographic distribution of fires in the Amazon rain forest and the rest of South America months in advance.

Though previous research has shown that human settlement patterns are the primary factor that drives the distribution of fires in the Amazon, the new research demonstrates that environmental factors – specifically small variations in ocean temperatures – amplify human impacts and underpin much of the variability in the number of fires the region experiences from one year to the next.

"Higher than normal sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic and the Pacific proved to be red flags that a severe fire season was on its way in four to six months," said Yang Chen, the University of California, Irvine, scientist who led the research. Chen and his colleagues found temperature changes of as little as .25°C (.45°F) in the North Atlantic and 1°C (1.8 °F) in the Central Pacific can be used to forecast the severity of the fire season across much of the Amazon.

The researchers believe that unusually warm sea surface temperatures cause regional precipitation patterns to shift north in the southern Amazon during the wet season. "The result is that soils don't get fully saturated. Months later, humidity and rainfall levels decline, and the vegetation becomes drier and more flammable," said James Randerson, a scientist at University of California, Irvine who co-authored the study.

UC Irvine scientist Jim Randerson discusses a new model that is able to predict fire activity in South America using sea surface temperature observations of the Pacific and Atlantic Ocean. The findings appear in the journal Science.

To establish the connection between fire activity and sea surface temperatures the researchers analyzed nine years of fire activity data collected by Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer instruments (MODIS) on NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites and compared the number of fires to records of sea surface temperatures maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Years with anomalously cool ocean temperatures had fewer fires, while years that experienced unusually warm ocean temperatures experienced more fires. The team also looked for and found changes in precipitations patterns as measured by the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM), a satellite managed jointly by NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

While a Columbia University-led study published in July of this year showed that sea surface temperatures in the Northern Atlantic could be used to forecast fire severity across the a small section of the western Amazon in Peru and Brazil, the new study considers a much broader swath of South America and takes into account how ocean temperatures in both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans affect the continent's fires.

The University of California, Irvine team also developed and validated an innovative computer model that they used to predict 2010 fire activity and could be used to forecast fire season severity in the future. The team's model successfully predicted that prolonged drought and severe fires would occur during the 2010 fire season, which is exactly what happened.

"Fire activity can vary dramatically. Satellites detected about twice as many fires during 2010 as they did in 2009," said Doug Morton, a scientist based at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. who coauthored the new study. The researchers have to wait a few more months before they can determine whether the model's predictions for the 2011 fire season were also accurate.

"For the 2010 season, the model successfully captured not only the severity of wildfire activity, but it also got much of the east-west spatial distribution right," said Randerson. By looking back at a full decade of data, the scientists noticed a distinctive pattern: fires in the southern and southwestern part of the Amazon were most strongly influenced by sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic, but fires in the eastern part of the Amazon were strongly affected by sea surface temperatures in the central Pacific.

A number of different types of fires occur in the region, including fires for deforestation, agricultural management, and wildfires in savannas and tropical forests. In addition to successfully predicting the overall fire severity, the model also captured the variability in forest and savanna fires from one year to the next when considered separately.

The researchers are optimistic that the findings may help serve as the foundation of an early warning system for fires that would help South American authorities prepare for severe fire seasons. Morton noted an early warning system could play a critical role in helping authorities blunt the negative impacts of heavy fires years such as those the region has experienced in 2005, 2007, and 2010.

Fire activity is a growing concern in the Amazon, a humid region that would experience very few fires in the absence of human activity. "Deforestation rates in the Amazon have declined significantly in recent years due to government regulations, but fire activity has been holding steady and even going up in some areas due to increases in escaped agricultural fires," said Ruth DeFries, a scientist at Columbia University, New York, and a co-author on the paper.

South American fires have a particularly important impact on climate. Fires from deforestation contribute about half of the carbon emissions from deforestation in South America and a recent analysis showed that for the continent creates about 15 percent of the worldwide carbon emissions from fires. Climate models predict that the region will receive less rainfall as climate change progresses, which would increase the risk of forest fires and lead to greater carbon emissions.

The study was published in the Nov. 11th edition of Science. Researchers from Duke University, Columbia University, and the University of Maryland are also coauthors on the study.

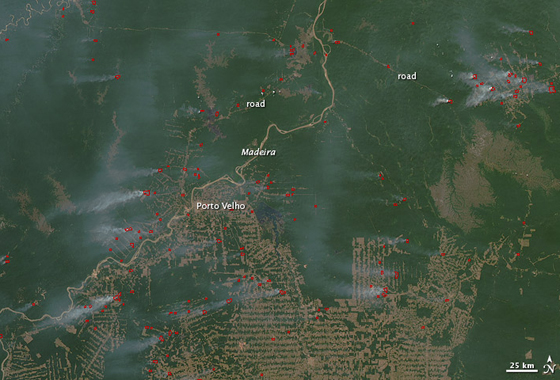

This visualization shows nearly a decade of active fire data in South America as observed by instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites. Credit: NASA/Scientific Visualization Studio.