News | September 22, 2008

Southern Californians get a cool summer, but a warm future

Summer 2008 in Southern California goes down in the books as cooler than normal. The thermometer in downtown Los Angeles topped 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32.2 degrees Celsius) just once in July, August and the first two-thirds of September. But don't expect this summer's respite from the usual blistering heat to continue in the years to come, cautions a group of NASA and university scientists: The long-term forecast calls for increased numbers of scorching days and longer, more frequent heat waves.

Our snow pack will be less, our fire seasons will be longer, and unhealthy air alerts will be a summer staple.

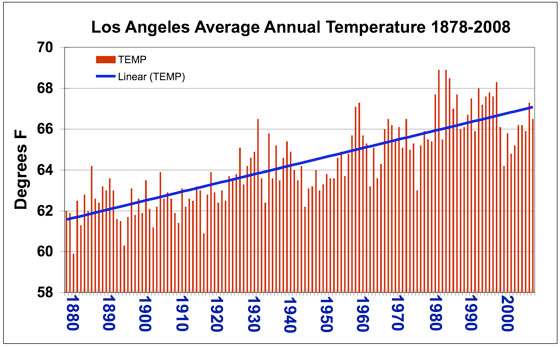

One hundred years of daily temperature data in Los Angeles were analyzed by scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.; the University of California, Berkeley; and California State University, Los Angeles. They found that the number of extreme heat days (above 90 degrees Fahrenheit or 32.2 degrees Celsius in downtown Los Angeles) has increased sharply over the past century. A century ago, the region averaged about two such days a year; today the average is more than 25. In addition, the duration of heat waves (two or more extreme heat days in a row) has also soared, from two-day events a century ago to one- to two-week events today.

"We found an astonishing trend - a dramatic increase in the number of heat waves per year," says Arbi Tamrazian, lead author of the study, and a senior at the University of California, Berkeley.

Tamrazian and his colleagues analyzed data from Pierce College in Woodland Hills, Calif., and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power in downtown Los Angeles. They tracked the number of extreme heat days and heat waves from 1906 to 2006. The team found that the average annual maximum daytime temperature in Los Angeles has risen by 5 degrees Fahrenheit (2.8 degrees Celsius) over the past century, and the minimum nighttime temperature has increased nearly as much. They also found that heat waves lasting six or more days have been occurring regularly since the 1970s. More recently, two-week heat waves have become more common.

"The bottom line is that we're definitely going to be living in a warmer Southern California," says study co-author Bill Patzert, a JPL climatologist and oceanographer. "Summers as we now know them are likely to begin in May and continue into the fall. What we call 'scorcher' days today will be normal tomorrow. Our snow pack will be less, our fire seasons will be longer, and unhealthy air alerts will be a summer staple.

"We'll still get the occasional cool year like this year," Patzert continued, "but the trend is still towards more extreme heat days and longer heat waves."

So what's behind this long-term warming trend? Patzert says global warming due to increasing greenhouse gases is responsible for some of the overall heating observed in Los Angeles and the rest of California. Most of the increase in heat days and length of heat waves, however, is due to a phenomenon called the "urban heat island effect."

Heat island-induced heat waves are a growing concern for urban and suburban dwellers worldwide. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, studies around the world have shown that this effect makes urban areas from 2 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit (1 to 6 degrees Celsius) warmer than their surrounding rural areas. Patzert says this effect is steadily warming Southern California, though more modestly than some larger urban areas around the world.

"Dramatic urbanization has resulted in an extreme makeover for Southern California, with more homes, lawns, shopping centers, traffic, freeways and agriculture, all absorbing and retaining solar radiation, making our megalopolis warmer," Patzert said.

These trends may capture the attention of utility companies and public health officials. "We'll be using more power and water to stay cool," says study co-author Steve LaDochy of California State University, Los Angeles. "Extreme heat, both day and night, will become more and more dangerous, even deadly."

The findings are published in the July 2008 issue of the Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers. JPL oceanographer and climate scientist Josh Willis was also a co-author on the research.