5 min read

This video shows aerosol emission and transport from September 1, 2006 to April 10, 2007. Also included are locations, indicated by red and yellow dots, of wildfires and human-initiated burning as detected by the MODIS instrument on NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites. Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Download the animation here.

The residents of Beijing and Delhi are not the only ones feeling the effects of Asian air pollution — an unwanted byproduct of coal-fired economic development. The continent's tainted air is known to cross the Pacific Ocean, adding to homegrown air-quality problems on the U.S. West Coast.

But unfortunately, pollution doesn't just pollute. Researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the California Institute of Technology, both in Pasadena, California, are looking at how Asian pollution is changing weather and climate around the globe.

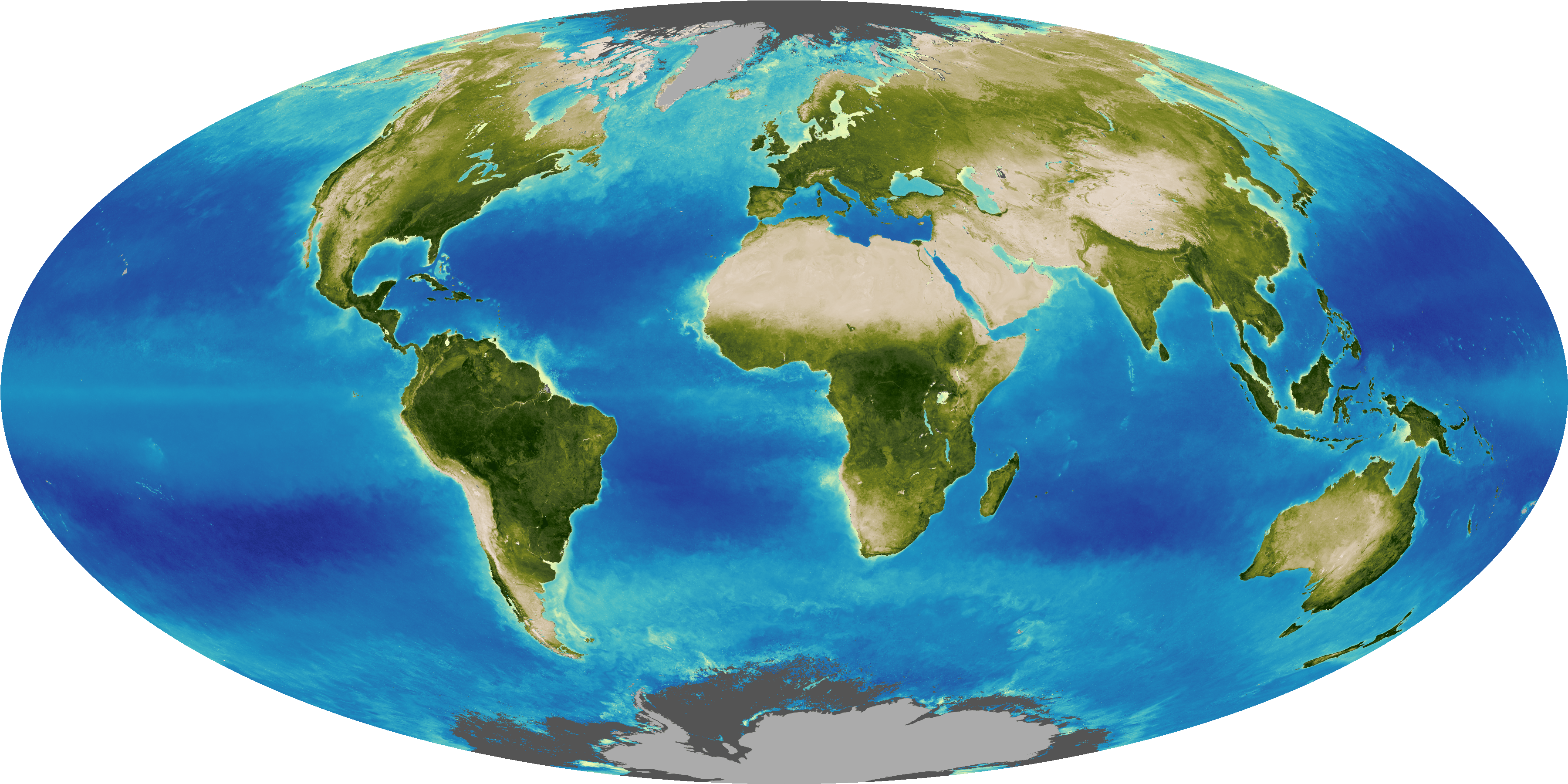

Scientists call airborne particles of any sort — human-produced or natural — aerosols. The simplest effect of increasing aerosols is to increase clouds. To form clouds, airborne water vapor needs particles on which to condense. With more aerosols, there can be more or thicker clouds. In a warming world, that's good. Sunlight bounces off cloud tops into space without ever reaching Earth's surface, so we stay cooler under cloud cover.

But that simplest effect doesn't always happen. If there's no water vapor in the air — the air is dry — aerosols can't make clouds. Different types of aerosols have different effects, and the same aerosol can have different effects depending on how much is in the air and how high it is. Soot particles at certain altitudes can cause cloud droplets to evaporate, leaving nothing but haze. At other altitudes, soot can cause clouds to be deeper and taller, producing heavy thunderstorms or hailstorms. With so many possibilities, aerosols are one of the largest sources of uncertainty in predicting the extent of future climate change.

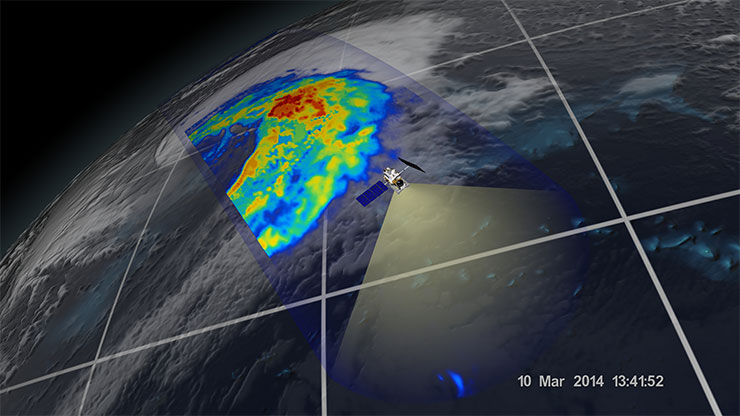

During the last 30 years, clouds over the Pacific Ocean have grown deeper, and storms in the Northwest Pacific have become about 10 percent stronger. This is the same time frame as the economic boom in Asia. JPL researcher Jonathan Jiang and his postdoctoral fellow, Yuan Wang, designed a series of experiments to see if there was a connection between the two phenomena.

They used a numerical model that included weather factors such as temperature, precipitation and barometric pressure over the Pacific Ocean as well as aerosol transport — the movement of aerosols around the Earth. They did two sets of simulations. The first used aerosol concentrations thought to have existed before the Industrial Revolution. The other used current aerosol emissions. The difference between the two sets showed the effects of increased pollution on weather and climate.

"We found that pollution from China affects cloud development in the North Pacific and strengthens extratropical cyclones," said Wang. These large storms punctuate U.S. winters and springs about once a week, often producing heavy snow and intense cold.

Wang explained that increased pollution makes more water condense onto aerosols in these storms. During condensation, energy is released in the form of heat. That heat adds to the roiling upward and downward airflows within a cloud so that it grows deeper and bigger.

"Large, convective weather systems play a very important role in Earth's atmospheric circulation," Jiang said, bringing tropical moisture up to the temperate latitudes. The storms form about once a week between 25 and 50 degrees north latitude and cross the Pacific from the southwest to the northeast, picking up Asia's pollutant outflow along the way.

Wang thinks the cold winter that the U.S. East endured in 2013 probably had something to do with these stronger extratropical cyclones. The intense storms could have affected the upper-atmosphere wind pattern, called the polar jet stream.

Jiang and Wang are now working on a new experiment to analyze how increased Asian emissions are affecting weather even farther afield than North America. Although their analysis is in a preliminary stage, it suggests that the aerosols are having a measurable effect on climatic conditions around the globe.

How much these climate effects will increase in the coming decades is an open question. How much they can be reversed if emissions are reduced in Asia also remains unclear.

The researchers pointed out that their work should raise even more red flags about aerosol-based geoengineering solutions — interventions in the Earth system intended to counteract global warming. Some groups have suggested that we could inject sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere to block incoming sunlight, but Jiang and Wang found that sulfates are the most effective type of aerosol for deepening extratropical cyclones. Ongoing injections would bring more stormy winter weather globally and would likely change the climate in other ways we cannot yet foresee.

Jiang noted that Asian emissions have made him and some other climate researchers conceptualize Earth differently. "Before, we thought about the North-South contrast: the Northern Hemisphere has more land, the Southern Hemisphere has more ocean. That difference is important to global atmospheric circulation. Now, in addition to that, there's a West-East contrast. Europe and North America are reducing emissions; Asia is increasing them. That change also affects the global circulation and perturbs the climate."