News | November 16, 2014

NASA computer model provides a new portrait of carbon dioxide

Plumes of carbon dioxide in the simulation swirl and shift as winds disperse the greenhouse gas away from its sources. The simulation also illustrates differences in carbon dioxide levels in the northern and southern hemispheres and distinct swings in global carbon dioxide concentrations as the growth cycle of plants and trees changes with the seasons.

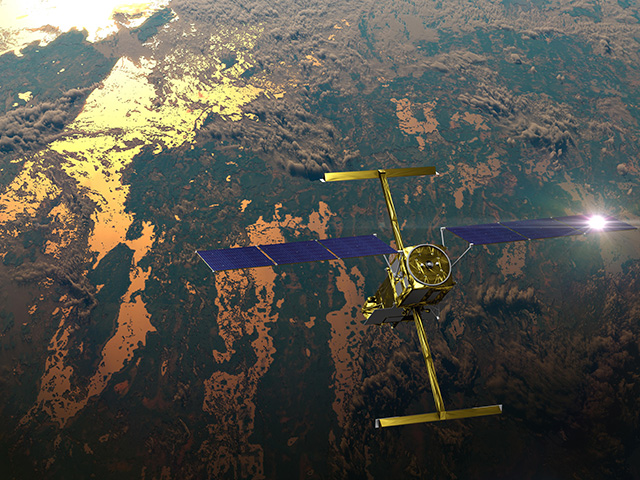

Scientists have made ground-based measurements of carbon dioxide for decades and in July NASA launched the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) satellite to make global, space-based carbon observations. But the simulation — the product of a new computer model that is among the highest-resolution ever created — is the first to show in such fine detail how carbon dioxide actually moves through the atmosphere.

“While the presence of carbon dioxide has dramatic global consequences, it’s fascinating to see how local emission sources and weather systems produce gradients of its concentration on a very regional scale,” said Bill Putman, lead scientist on the project from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “Simulations like this, combined with data from observations, will help improve our understanding of both human emissions of carbon dioxide and natural fluxes across the globe.”

The carbon dioxide visualization was produced by a computer model called GEOS-5, created by scientists at NASA Goddard’s Global Modeling and Assimilation Office. In particular, the visualization is part of a simulation called a “Nature Run.” The Nature Run ingests real data on atmospheric conditions and the emission of greenhouse gases and both natural and man-made particulates. The model is then is left to run on its own and simulate the natural behavior of the Earth’s atmosphere. This Nature Run simulates May 2005 to June 2007.

While Goddard scientists have been tweaking a “beta” version of the Nature Run internally for several years, they are now releasing this updated, improved version to the scientific community for the first time. Scientists are presenting a first look at the Nature Run and the carbon dioxide visualization at the SC14 supercomputing conference this week in New Orleans.

“We’re very excited to share this revolutionary dataset with the modeling and data assimilation community,” Putman said, “and we hope the comprehensiveness of this product and its ground-breaking resolution will provide a platform for research and discovery throughout the Earth science community.”

In the spring of 2014, for the first time in modern history, atmospheric carbon dioxide — the key driver of global warming — exceeded 400 parts per million across most of the northern hemisphere. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, carbon dioxide concentrations were about 270 parts per million. Concentrations of the greenhouse gas in the atmosphere continue to increase, driven primarily by the burning of fossil fuels.

Despite carbon dioxide’s significance, much remains unknown about the pathways it takes from emission source to the atmosphere or carbon reservoirs such as oceans and forests. Combined with satellite observations such as those from NASA’s recently launched OCO-2, computer models will help scientists better understand the processes that drive carbon dioxide concentrations.

The Nature Run also simulates winds, clouds, water vapor and airborne particles such as dust, black carbon, sea salt and emissions from industry and volcanoes.

The resolution of the model is approximately 64 times greater than that of typical global climate models. Most other models used for long-term, high-resolution climate simulations resolve climate variables such as temperatures, pressures, and winds on a horizontal grid consisting of boxes about 50 kilometers (31 miles) wide. The Nature Run resolves these features on a horizontal grid consisting of boxes only 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) wide.

The Nature Run simulation was run on the NASA Center for Climate Simulation’s Discover supercomputer cluster at Goddard Space Flight Center. The simulation produced nearly four petabytes (million billion bytes) of data and required 75 days of dedicated computation to complete.

In addition to providing a striking visual description of the movements of an invisible gas like carbon dioxide, as it is blown by the winds, this kind of high-resolution simulation will help scientists better project future climate. Engineers can also use this model to test new satellite instrument concepts to gauge their usefulness. The model allows engineers to build and operate a “virtual” instrument inside a computer.

Using GEOS-5 in tests known as Observing System Simulation Experiments (OSSE) allows scientists to see how new satellite instruments might aid weather and climate forecasts.

“While researchers working on OSSEs have had to rely on regional models to provide such high-resolution Nature Run simulations in the past, this global simulation now provides a new source of experimentation in a comprehensive global context,” Putman said. “This will provide critical value for the design of Earth-orbiting satellite instruments.”