Ask NASA Climate | June 13, 2013, 14:59 PDT

Global warming consensus

Agreement among scientists confirmed again

By Erik Conway, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

A new paper has revisited the question of whether there’s a consensus among climate scientists about the reality of anthropogenic (human-caused) global warming (AGW). The study, by John Cook, of the University of Queensland’s Global Change Institute in Australia and the Skeptical Science site, and several co-authors, confirms that climate scientists have not only accepted the existence of global warming, but also its human causation, as a matter of fact for the last two decades.

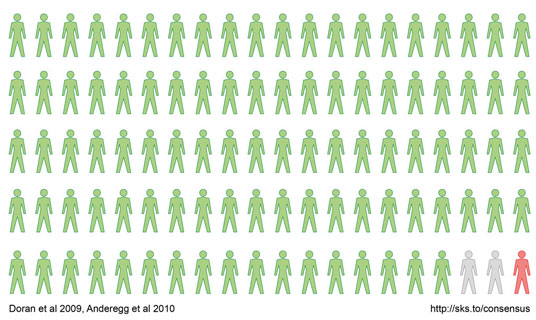

Drawing from 11,944 climate science abstracts from scientific journals between 1991 and 2011, the team found 66.4 percent of the abstracts expressed no opinion, 32.6 percent explicitly endorsed AGW, 0.7 percent rejected it and 0.3 percent expressed uncertainty on the cause of global warming. Then the authors invited a subset of these papers’ authors to place their own papers into the same categories that Cook and his collaborators had used. These authors overwhelmingly endorsed the statement that most of the past century’s warming was caused by human greenhouse gas emissions.

This isn’t a terribly surprising result. As the authors acknowledge, Naomi Oreskes found the same overwhelming consensus back in 2004 (though with a much smaller sample size). The methodology underlying the two papers differs, especially in that Cook and colleagues used a web-based, randomized abstract distribution and review process — and polled individual authors as a second check on their categorization. But the result, like several survey-based papers published in the last few years, is essentially the same. Climate scientists agree that humans are causing climate change, and they have agreed on this for some time.

Perhaps the one new finding in this paper is the quantitative demonstration that the consensus existed by 1991. Again, I don’t find this surprising. The National Academy of Science’s 1979 report, "Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Scientific Assessment," found “no reason to doubt that climate change will result, and no reason to believe that those changes will be negligible” from a continuing buildup of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere. Oreskes’ results also indicate that the consensus among publishing researchers was in place by the early 1990s. But further quantitative confirmation that these earlier studies were not far out on a limb is nice to have.

This latest publication by Cook and co. has resulted in a kerfuffle among some of the climate-change-friendly bloggers that I think is worth mentioning. One blogger I follow closely, Dan Kahan of the Cultural Cognition Project at Yale University, has expressed unhappiness about it on the grounds that re-determining or re-emphasizing the existence of consensus doesn’t advance climate science communication. Kahan and I, like most social scientists, are opponents of what’s known as the “deficit model” of science communication, which posits that people are empty vessels into which one can simply pour facts. Rather, I believe that people accept, or reject, new information mostly on the basis of their pre-existing knowledge and beliefs. So merely telling the average citizen that 97 percent of climate scientists believe that humans are causing climate change isn’t likely to change many minds about the issue.

But some polls and market research have shown that, for quite a few people, their views about government action change when they think the science is settled. This was a key finding of market research sponsored by the Western Fuels Association, a coal industry trade association, in the early 1990s — just as the scientific consensus on anthropogenic warming was emerging — and a major reason why they funded campaigns to persuade the American people that the science was unsettled. The idea was (and remains) to challenge the science to prevent action. And it was, of course, the guiding idea behind tobacco industry disinformation campaigns as well. So to the extent that this strategy works, it’s important to continue to point out that it is based on a fallacy.

I do think there’s more that Cook et al. could draw out of the data they’ve collected. I have a hypothesis that different disciplines within climate science reached consensus at different times: radiative transfer specialists in the 1980s, atmospheric scientists by the mid-1990s, physical oceanographers and cryosphere researchers in the early 2000s, etc. I don’t have the data to test that hypothesis quantitatively, but I think Cook and his collaborators now do. I hope they take on the challenge, as that would be a worthwhile expansion of our knowledge about the historical development of this important science.

References/Further Reading:

John Cook et al., “Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature,” Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 024024 (2013), doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024.

Naomi Oreskes, “The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change,” Science Vol. 306, no. 5702, p. 1686 (3 December 2004), doi: 10.1126/science.1103618.

Ad Hoc Study Group on Carbon Dioxide and Climate, "Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Scientific Assessment," National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC (1979), quote from p. viii.

Naomi Oreskes, “My facts are better than your facts: Spreading good news about global warming,” in “How Well Do Facts Travel?”, Cambridge University Press, pp. 136-166 (2010), doi:10.1017/CBO9780511762154.008.